Definition of an “Energy Dispute” according to the Energy Charter Treaty

First proposed in 1990, at the European Energy Council in Dublin, the European Energy Charter was transformed into a legally binding document – the Energy Charter Treaty (ECT or Treaty) in 1994.[1] The ECT entered into force in April 1998 and has currently fifty-three Signatories and Contracting Parties to the Treaty, including the European Union and Euratom.[2] The ECT was a one of its kind multilateral investment protection agreement at the time of the adoption, as it sought to promote international cooperation in one specific industry – the energy sector.[3] While its historical objective – creation of a legal framework for the cooperation on energy matters between the USSR, the countries of the Central and Eastern Europe and the West[4] - has been outpaced, it continues to play a decisive role for the cross-border cooperation in the energy sector offering a legal framework which provides foreign investment protection mechanisms and their enforcement through international arbitration.

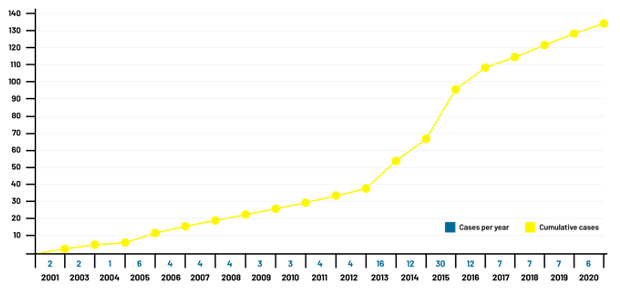

As of 9 October 2020, the Energy Charter Secretariat has reported to be aware of 134 investment arbitration cases which have been instituted under the Treaty.[5] No other international trade and investment agreement has apparently triggered more investment arbitration proceedings. The number of cases has rapidly increased in the last decade and is likely to rise in view of the expected legislative changes related to the low-carbon transition:

Source: An explosion of cases. ECT’s dirty secrets.[6]

Keeping in mind the initial objective of the Treaty, it is worth noting that, as of 2013, the majority of claims have been filed against the Western European countries.[7] In addition, despite the reported primary design of the Treaty for the fossil fuels industry, the majority of claims under the ECT arose out of the alleged electricity breaches related to changes in incentives in electricity production from the renewable energy sources.[8]

In view of the continuing importance of the Treaty, this contribution has been drafted based on the speaking notes for the presentation during the joint Stockholm Chamber of Commers and Ukrainian Arbitration Association webinar on ECT Disputes.[9] It focuses on a very limited aspect of the scope of the Treaty’s protection – the definition of the notion of an “Energy Dispute” – a task which has been defined for the webinar in view of the lengthy definitions and not particularly user-friendly complex structure of the Treaty and related documents.[10] For this purpose, the contribution will first briefly map the overall scope of protection under the ECT and the legal definition of the “Economic Activity in the Energy Sector”. Then, selected cases addressing this notion will be presented. Concluding, the article briefly addresses possible changes to the ECT in view of the ongoing modernisation process.

Scope of Protection

The ECT Treaty does not contain a definition of an “Energy Dispute”. Part III of the Treaty comprises provisions on investment protection applicable to “Investments of Investors” enforceable according to Articles 26-28 ECT.[11] In other words, the scope of protection pursuant to Part III of the ECT delineates the right to arbitration under Article 26 ECT, since the Investor’s right to arbitration is limited to disputes between a “Contracting Party” and an “Investor” of another “Contracting Party” relating to an ‘“Investment”‘ of the “Investor” in the Area of the first “Contracting Party”.

Article 1 (7) ECT defines the notion of “Investor” as a natural person having the citizenship or nationality of or who is permanent resident in that Contracting Party in accordance with its applicable law; or a company or other organisation organised in accordance with the law applicable in that Contracting Party. Article 1 (6) ECT defines a very broad notion of “Investment”, referring to any kind of asset, which is owned or controlled directly or indirectly by an Investor and includes: “(a) tangible and intangible, and movable and immovable, property, and any property rights such as leases, mortgages, liens, and pledges; (b) a company or business enterprise, or shares, stock, or other forms of equity participation in a company or business enterprise, and bonds and other debt of a company or business enterprise; (c) claims to money and claims to performance pursuant to a contract having an economic value and associated with an Investment; (d) Intellectual Property; (e) Returns; (f) any right conferred by law or contract or by virtue of any licenses and permits granted pursuant to law to undertake any Economic Activity in the Energy Sector.

Article 1 (6) ECT also stipulates that

“Investment” refers to any investment associated with an Economic Activity in the Energy Sector and to investments or classes of investments designated by a Contracting Party in its Area as “Charter efficiency projects” and so notified to the Secretariat.” (emphasis added)

Thus, the definition of Investment in the first part of Article 1(6) is very broad and inclusive. The requirement of an “association with” the energy sector restriction in the final part of Article 1(6) is rather open-textured. Accordingly, the Treaty does not require an Investment to be an Economic Activity in the Energy Sector, but only to be associated with the latter. Article 1 (5) ECT in its turn defines the notion of the “Economic Activity in the Energy Sector” as follows:

“Economic Activity in the Energy Sector” means an economic activity concerning the exploration, extraction, refining, production, storage, land transport, transmission, distribution, trade, marketing, or sale of Energy Materials and Products except for those included in Annex NI, or concerning the distribution of heat to multiple premises.”

The Treaty thereby does not limit the sources of energy. Further regulations with regard to the Economic Activity in the Energy Sector can be found in the so-called Understandings comprised in the Final Act of the European Energy Charter Conference. Understanding 2 with respect to Article 1 (5) ECT clarifies that the Treaty confers no right to engage in economic activities other than Economic Activities in the Energy Sector. At the same time, it provides the following, non-exhaustive illustrative list of Economic Activities in the Energy Sector:

(i) Prospecting and exploration for, and extraction of, e.g. oil, gas, coal and uranium;

(ii) Construction and operation of power generation facilities, including those powered by wind and other renewable energy sources;

(iii) Land transportation, distribution, storage and supply of Energy Materials and Products, e.g., by way of transmission and distribution grids and pipelines or dedicated rail lines, and construction of facilities for such, including the laying of oil, gas, and coal slurry pipelines;

(iv) Removal and disposal of wastes from energy related facilities, including oil rigs, oil refineries and power generation plants;

(v) Marketing and sale of, and trade in Energy Materials and Products, e.g., retail sales of gasoline; and

(vi) Research, consulting, planning, management and design activities related to activities mentioned above, including those aimed at Improving Energy Efficiency.[12]

Articles 1 (4) and (4bis) ECT refer to Annexes EM I and EM II as well as Annexes EQ I and EQ II for the list of items falling within the definition of “Energy Materials and Products” and “Energy-Related Equipment” respectively. A protected Energy Material and Product, as well as Energy-Related Equipment have to be included into these lists and shall not be excluded by Annex NI. Annex EM I contains a very detailed list of various Energy Materials and Products related to nuclear energy and coal, natural gas, petroleum and petroleum products, electrical energy and other energy, including fuel wood and wood charcoal. Annex EQ I includes a 17-pages long list of Energy-Related Equipment.

The Notion of “Investment Associated with an Economic Activity in the Energy Sector” in Case Law

Despite the detailed lists and examples of investments associated with an Economic Activity in the Energy Sector, based on publicly available information, a number of Arbitral Tribunals dealt with jurisdictional challenges based on the arguments that an activity in question did not qualify as an Investment under the ECT because the activity either did not qualify as an “Economic Activity in the Energy Sector” or because the Investment was not “associated” with the latter. Below examples demonstrate how selected Arbitral Tribunals dealt with such challenges in practice and provide some guidance on possible interpretation of the ECT.

Amto v Ukraine

In a dispute between a Limited Liability Company Amto against Ukraine, the Arbitral Tribunal dealt with a jurisdictional objection challenging the existence of an investment and whether undertakings of Claimant constituted an associated Economic Activity in the Energy Sector.[13] The dispute arose out of the bankruptcy of the Zaporozhskaya nuclear power plant (ZAES) and its default under contracts to claimant’s subsidiary for maintenance works carried out at the plant.

Ukraine contested jurisdiction of the Tribunal, arguing that Amto’s shares in the Ukrainian company EYUM-10 did not constitute a qualified “Investment” under the ЕСТ, since they were not “associated with an Economic Activity in the Energy Sector”, as required by Article 1(6) ЕСТ.[14] Respondent stated that EYUM-10’s activities, which consisted of electric installation works, repair, reconstruction and technical re-equipment works and services to ZAES, did not fall within any of the categories listed in Article 1(5) ЕСТ, which constituted the controlling definition of “Economic Activity in the Energy Sector”, and also did not fall within the illustrative list of “Economic Activity in the Energy Sector” presented in the Understandings IV.2.b.ii of the Final Act of the European Energy Charter Conference.[15] Respondent argued that Understanding 2 to the Final Act Energy Charter Conference included illustrative list of Economic Activities in the Energy Sector, inter alia, referring to “construction and operation of power generation facilities” and emphasised that the Understandings were not part of the ЕСТ and could not be used to extend or modify the definition in Article 1(5) ECT.[16] Further, Respondent added that “construction and operation” were a compound and single standard and if the Claimant’s activities amounted to construction they did not involve or concern the operation of power generation facilities.[17]

In addition, Respondent stated that Amto’s shares in EYUM-10 were not sufficiently closely “associated with” an economic activity of ZAES/Energoatom in the energy sector, such as the production (or sale) of Energy Materials and Products.[18] Respondent purported that the ЕСТ did not protect “investments remotely or loosely related to Economic Activity in the Energy Sector” and referred to the fact that ZAES/Energoatom had multiple contractual relationships.[19] Respondent indicated that it was not the object and purpose of the ЕСТ to extend investment protection to ordinary commercial transactions.[20] Respondent further argued that an Investment “should have stable, long-term, intensive episodic, fragmentary, incidental, etc” and indicated that EYUM-10’s short term case-by-case relationships with ZAES in respect of repair and reconstruction works did not have such integrity and stability as to justify ЕСТ protection.[21]

Claimant in its turn argued that its ownership of shares in EYUM-10, pursuant to the broad definition laid down in Article 1(6) ЕСТ, constituted an Investment, and hence, Amto qualified as an Investor under Article 1(7).[22] Furthermore, Claimant stated that Amto’s Investment, i.e. the ownership of shares in EYUM10, “was associated with an Economic Activity in the Energy Sector”. Claimant also indicated that EYUM-10 provided qualified construction and maintenance services to the nuclear industry in Ukraine, and according to the illustrative list contained in Understanding No 2, such work should be deemed to constitute an “Economic Activity in the Energy Sector” pursuant to Article 1(5) ЕСТ.

Having mapped out the regulatory framework and having assessed the evidence, the Arbitral Tribunal confirmed that that EYUM-10’s contracts related to electrical installation, repairs and technical reconstruction or upgrading - the provision of technical services - at the ZAES nuclear power plant.[23] The Arbitral Tribunal also considered that the interpretation of the words „associated with“ involved a question of degree, and referred primarily to the factual rather than legal association between the alleged investment and an Economic Activity in the Energy Sector.[24] The Tribunal proceeded with stating that a mere contractual relationship with an energy producer would be insufficient to attract ЕСТ protection where the subject-matter of the contract had no functional relationship with the energy sector. The Arbitral Tribunal further found that the open-textured phrase „associated with“ must be interpreted in accordance with the object and purpose of the ЕСТ, as expressed in Article 2 ECT, thus, finding that the associated activity of any alleged investment must be energy related, without itself needing to satisfy the definition in Article 1(5) of an Economic Activity in the Energy Sector.[25]

The Tribunal found that ZAES/Energoatom was engaged in an Economic Activity in the Energy Sector as its activity concerned the production of Energy Material and Products, namely electrical energy.[26] The Arbitral Tribunal went on to underline that EYUM-10 provided technical services - installation, repair and upgrades – which were directly related to the production of electrical energy and were provided through multiple contracts over a substantial period of time.[27] The Arbitral Tribunal referred to the case specific evidence, i.e. a letter to EYUM-10 dated 28 February 2002 in which ZAES had described EYUM-10 as being a „strategic partner for 20 years“ and had stated that EYUM-10’s services were „strategically important and directed on the reliable and safe exploitation of power units of our nuclear power plant.”[28] The Tribunal then went on to find that the close association of EYUM-10 with ZAES in the provision of services directly related to energy production meant that Amto’s shareholding in EYUM-10 was an „investment associated with an Economic Activity in the Energy Sector” and, thus, qualified as an Investment within the meaning of the Treaty.[29]

Electrabel S.A. v Hungary

In a dispute following the Hungary’s termination of a power purchase agreement concluded with the investor, arguably as part of the State’s program for liberalizing its electricity market to comply with EU laws on State aid, the Arbitral Tribunal weighed in on the definition of Investment according to Article 1 (6) ECT in view of the requirement for the Investment to be “associated with an Economic Activity in the Energy Sector”.[30]

With regard to the electricity generation, the Tribunal noted that it was clear from the ordinary meaning of the term that electricity generation constituted an Economic Activity in the Energy Sector.[31] The Arbitral Tribunal further found that, in accordance with the definition contained in Article 1(5) ECT and provisions of Annex EM paragraph 27.16 ECT and Annex NI ECT, the activities of “production” and “sale” of “electrical energy” as “energy materials” also constituted an “Economic Activity in the Energy Sector.”[32]

The Arbitral Tribunal then proceeded with addressing the disagreement between the Parties with regards to the application of Article 1 (6) (c) and (f) ECT to the power purchase agreement in question (PPA).[33] Article 1 (6) (c) ECT defines as an “Investment” contractual claims to money or performance, having an economic value and associated with an investment. The Arbitral Tribunal found that the PPA comprised contractual claims to money, constituted by the capacity and energy fees, as well as contractual claims to performance, which also had an economic value.[34] With regard to the Parties disagreement as to what extent the limitation of the phrase “associated with an investment” gave rise to circularity in the ECT’s definition of “Investment” (“Investment … includes … claims … associated with investment”), the Tribunal stated the following:

“Under the Vienna Convention, the correct interpretation must give effect to the terms in their context and avoid obscure results. To this end, as a matter of common sense in their context and avoid obscure results. To this end, as a matter of common sense, it is necessary to understand “investment” in sub-paragraph (c) to mean an investment other than the one addressed in this same sub-paragraph. In the present case, the Tribunal considers the rights arising out of the PPA to be associated with the Claimant’s overall investment described above. In other words, the Tribunal agrees with the Respondent’s submission and decides that this category of investment is dependent on the overall investment.”[35]

The Tribunal further indicated that its position was supported by the decision of the Tribunal in Amco v Ukraine:

“In that case, ZAES/Energoatom constituted the overall investment and its activity concerned the production of electrical energy. Although Ukraine argued that Amto’s shareholding in another company (which provided technical services to ZAES) did not constitute an investment under the ECT since its operations were not “associated” with an economic activity in the energy sector, the tribunal concluded that the association of the technical services provider with ZAES was directly related to energy production; and Amto’s shareholding in the service provider was thus considered as an “investment” under the ECT.”[36]

Finally, the Arbitral Tribunal ruled that the PPA Termination Claim met the requirements of Article 1 (6) (f) ECT, as it the PPA constituted a commercial agreement to undertake the sale and distribution of electricity and was thus „associated” with an economic activity in the energy sector.[37] The Tribunal concluded that the right to undertake electricity sales and distribution pursuant to Hungarian law was associated with an Economic Activity in the Energy Sector and as such constituted an Investment under Article 1 (6) (f) ECT.[38]

Energoalliance Ltd v Moldova

In a dispute arising out of the non-payment of accumulated debt by the State-owned entity Moldtranselectro and by another former partner of Energoalians for the supplied energy, the Arbitral Tribunal briefly touched upon the notion of “association” of an Investment with an “Economic Activity in the Energy Sector” finding that an activity directly resulting from the sale of electricity fulfilled this requirement.[39] Having considered the arguments of Respondent stating that the supply of electricity could not constitute an “Investment” as contracts for the sale of goods are not “Investments” covered by the ECT protection, the Tribunal found that Claimant’s “Investment” was “associated with Economic Activity in the Energy Sector.”[40] Arriving at this decision, the Arbitral Tribunal noted that trade in electricity fell within the definition of the term of “Economic Activity in the Energy Sector” and that Claimant’s rights were “associated” with such activity as they emerged as a direct result of the sale of electricity.[41]

Blusun S.A., et al. v Italy

In a dispute arising out of the legislative reforms affecting the renewable energy sector in Italy, the Arbitral Tribunal addressed requirements of Article 1 (5) and (6) ECT, responding to the jurisdictional objection of Respondent based on the argument that Claimant’s activity did not qualify as an Economic Activity in the Energy Sector as it was related to activities preceding’s the actual construction of a power plant that were a mere “precondition for the realization of an ambitious project that would produce an effect”. [42]

The Arbitral Tribunal first turned to the broad definition of “Investment” according to Article 1 (6) ECT indicating that it applied to “any investment associated with an Economic Activity in the Energy Sector”.[43] Following the definition of the “Economic Activity in the Energy Sector”, the Tribunal resorted to the Understandings identifying “construction and operation of power generation facilities, including those powered by wind and renewable energy sources” as such activity.[44] The Arbitral Tribunal went on to rule that “the words ‘construction and operation’ [did] not impose a cumulative requirement; if they did, an investor purchasing an already constructed plant would not be covered.” Applying the facts of the case, the Tribunal found that as long as the project was lawful and not merely speculative, I qualified as investment within the terms of Articles 1(5) and (6) ECT, “whatever the position with merely preparatory work, e.g. in the preparation of a tender or the negotiation of a concession, once an active process of construction of an energy project involving substantial resources [has been] commenced, the merely preparatory phase is over and the project qualifies as an investment.”.[45]

Above cases demonstrate that a facts specific differentiating approach might be necessary in order to establish whether an Investment in dispute is “associated with an Economic Activity in the Energy Sector”.

Modernisation of the Treaty and its possible implications

At the moment, the ECT is undergoing a modernisation process, which has been initiated back in 2018.[46] The modernisation mandate, inter alia, envisaged potential revision of Article 1 (5) and (6) ECT indicating that some international investment agreements required protected investments to fulfil specific characteristics, such as commitment of capital, an effective contribution to the host State’s economy, and a certain duration, and/or include a legality requirement, such as compliance with domestic laws, including anticorruption/bribery regulations. [47] In addition, the mandate indicated that some ECT annexes on energy products and materials could be updated and the definition of ‘economic activity in the energy sector’ (could be clarified.[48]

The initial positions of the Contracting Parties with regard to the proposed changes to the definition of the “Economic Activity in the Energy Sector” differed greatly, including suggestions to amend the definition in view of the required low-carbon transition and an opposition to make any changes at all.[49] The First Negotiation Round on the Modernisation of the Energy Charter Treaty took place on 6-9 July 2020 by videoconference.[50] Initial proposals and discussion papers were presented and discussed in detail by the delegations. The Parties, inter alia, discussed possible revision of the definition of “Economic Activity in the Energy Sector” and definition of “Investment”.[51]

On 26 October 2020, a Proposal of the EU for the modernisation of the Energy Charter Treaty has been leaked online suggesting implementing changes related to the definition of the Economic Activity in the Energy Sector.[52] The EU Proposal included an exception to the application of Part III of the Treaty to Energy Materials and Products in Annex EM I under the heading “Coal. Natural Gas. Petroleum and Petroleum Products. Electrical Energy”, subheadings 27.01 to 27.15, and to the production of Electrical energy (27.16) if it is produced from one of the products in subheadings 27.01 to 27.15. in relation to an Investment made in the Area of a Contracting Party after the date of entry into force or provisional application of the amendment to the Treaty.[53] At the same time, the EU proposed that the provisions of Part III of this Treaty shall apply until 31 December 2030 to the production of Electrical energy (27.16) produced from Petroleum gases and other gaseous hydrocarbons (27.11). through power plants and infrastructure enabling the use of renewable and low carbon gases and emitting less than 550 g of CO2 of fossil fuel origin per kWh of electricity in relation to such Investments.[54] If such Investments, however, replace existing Investments producing Electrical energy (27.16) from Energy Materials and Products under the subheadings 27.01 to 27.10, the provisions of Part III of the Treaty shall apply until 3l December 2040 according to the proposal.

The EU Proposal goes on to suggest that the provisions of Part III of the Treaty shall apply until 3l December 2040 to lnvestments in gas pipelines made in the Area of a Contracting Party after the date of entry into force or provisional application of the amendment to the Treaty, “provided that the pipelines are able to transport renewable and low-carbon gases, as well as hydrogen”.[55] Finally, the EU proposes that “ten years after the entry into force or provisional application of the amendment to the Treaty, the provisions of Part III of this Treaty shall cease to apply to Energy Materials and Products in Annex EM I under the headins “Coal. Natural Gas, Petroleum and Products, Electrical Energy”, subheadings 27.01 to 27.15, as well as to the production of Electrical energy (27.16) if it is produced from one of the products in subheading 27.01 to 27.15, in relation to any Investment made in the Area of a Contracting Party before the date of entry into force or provisional application of the amendment to the Treaty.”[56] The EU Proposal also includes amendments to Annex EM I in “Other Energy” section as well as the definition of the Energy-Related Equipment and Annex EQ I. In addition, the definition of the Economic Activity in the Energy Sector is proposed to be expanded by specifically referring to “the operation and maintenance of Energy-Related Equipment”.[57]

These aspects of the EU’s Proposal seem to be clearly motivated by the EU’s commitment to the Paris Agreement and the low-carbon transition.[58] In October, the EU Parliament also voted in favor of ending the investment protection in fossil fuels as a result of the ECT’s modernisation.[59] These developments show that, at least as far as the motivation of the European Union is concerned, the ECT might undergo substantial changes as a result of the modernisation. If implemented, the notion of the “Energy Related Economic Activity” and respective Annexes and Understandings might be amended to reflect the phasing-out of fossil fuels and incentivize the low-carbon transition.

However, whether any of these suggestions will be adopted at the end remains highly questionable. In order to amend the ECT an unanimous vote of the Contracting Parties is required – a rather daunting task in view of the different interests and positions presented at the table. In view of the continued dominant capital expenditure of the big oil and gas companies into fossil fuels (99,20 %)[60] on the one hand and increasing pressure with regard to the alignment with the Paris Agreement in some countries on the other, the modernisation process of the ECT remains an important process to observe, as it might have far-reaching consequences for the energy sector in the decades to come.[61]

Olga Hamama,

Arbitrator and Co-Founder

Dispute resolution boutique V29 Legal, Frankfurt am Main, Germany

[1] Guide to the Energy Charter Treaty, p 8, available at: https://investmentpolicy.unctad.org/international-investment-agreements/treaty-files/2427/download

[2] The Energy Charter Treaty, available at: www.energycharter.org.

[3] K Hobér, The Energy Charter Treaty, p 1.

[4] Guide to the Energy Charter Treaty, p 8

[5] As the parties to arbitration are not obliged to notify the Energy Charter Secretariat under Article 26 ECT of any disputes, the actual numbers of cases might differ and some awards remain confidential. See List of Cases, last updated on 6 October 2020, available at https://www.energychartertreaty.org/cases/list-of-cases/.

[6] For more statistics see ECT’s Dirty Secrets, available at: https://energy-charter-dirty-secrets.org/.

[7] ECT’s Dirty Secrets, States under attack – A legal nightmare for East and West, available at: https://energy-charter-dirty-secrets.org/.

[8] Dr Y Saheb, Modernization of the Energy Charter Treaty, 3 March 2020, available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4Z6PKIdL-2Q&t=1769s.

[9] ECT Disputes, a joint SCC and UAA webinar, 26 November 2020, available at; https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4YhjTt0uHgM&t=3781s

[10] The ECT is a complex treaty comprising 8 Parts, fifty Articles and fourteen Annexes, which constitute an integral part of the Treaty, in addition to 5 Decisions, 22 Understandings, 8 Declarations (adopted at the same time as the Treaty to assist in its interpretation and application) and Interpretations. The Treaty itself is Annex 1 to the Final Act of the European Charter Conference. The Decisions constitute Annex 2 to the Final Act of the European Charter Conference.

[11] The protection mechanisms of the Treaty thereby apply to the so-called “post-investment phase”, see K Hobér, Investment Arbitration and the Energy Charter Treaty, Journal of International Dispute Settlement, 2010, p 5.

[12] Final Act of the European Energy Charter Conference, Understanding 2.

[13] Limited Liability Company Amto v Ukraine (Amto v Ukraine), SCC Case No. 080/2005, Final Award, 26 March 2008; available at: https://www.italaw.com/sites/default/files/case-documents/ita0030.pdf.

[14] Amto v Ukraine, Final Award, para 26 a).

[15] Ibid.

[16] Ibid.

[17]Ibid, para 40.

[18] Ibid, para 26 a).

[19] Ibid, para 40.

[20] Ibid.

[21] Ibid.

[22] Ibid, para 26 a).

[23] Ibid.

[24] Ibid, para 42.

[25] Ibid.

[26] Ibid, para 43.

[27] Ibid.

[28] Ibid.

[29] Ibid.

[30] Electrabel S.A. v. Republic of Hungary, ICSID Case No. ARB/07/19 (Electrabel S.A. v Hungary), Decision on Jurisdiction, Applicable Law and Liability, 30 November 2012, available at: https://www.italaw.com/sites/default/files/case-documents/italaw1071clean.pdf.

[31] Electrabel S.A. v Hungary, Decision on Jurisdiction, Applicable Law and Liability, para 5.50.

[32] Ibid.

[33] Ibid.

[34] Ibid, para 5.52.

[35] Ibid, para 5.53.

[36] Ibid, para 5.54.

[37] Ibid, paras 5.55-5.57

[38] Ibid, para 5.58.

[39] Energoalliance Ltd v The Republic of Moldova, UNCITRAL ad hoc arbitration, Arbitral Award, 23 October 2013, para 225. Unofficial English translation available at: https://www.energychartertreaty.org/fileadmin/DocumentsMedia/Cases/27_Energoalians/Fin_Aw_Energoalia...

[40] Ibid.

[41] Ibid.

[42] Blusun S.A., Jaen-Pierre Lecordier and Michael Stein v Italian Republic, ICSID Case No. ARB/14/3, Award, 17 December 2016, para 262.

[43] Ibid, para 263.

[44] Ibid.

[45] Ibid.

[46] Decision of the Energy Charter Conference on Modernisation of the Energy Charter Treaty, 28 November 2017

[47] Ibid.

[48] Ibid.

[49] Decision of the Energy Charter Conference on Adoption by Correspondence – Policy Options for Modernisation of the ECT, 6 October 2019, available at: https://www.energycharter.org/fileadmin/DocumentsMedia/CCDECS/2019/CCDEC201908.pdf.

[50] For a comprehensive overview of the process, see Modernisation of the Treaty, available at: https://www.energychartertreaty.org/modernisation-of-the-treaty/.

[51] Public Communication on the First Negotiation Round on the Modernisation of the Energy Charter Treaty, 6-7 July 2020, available at: https://www.energychartertreaty.org/fileadmin/DocumentsMedia/Library/Public_communication_EN1.pdf.

[52] Council of the European Union, EU Text Proposal for the Modernisation of the Energy Charter Treaty, 26 October 2020, available at: https://www.politico.eu/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/Commission-Proposal-Economic-Activity-and-Scope-E....

[53] Ibid.

[54] Ibid.

[55] Ibid.

[56] Ibid.

[57] Council of the European Union, EU Text Proposal for the Modernisation of the Energy Charter Treaty, 26 October 2020.

[58] See EU Climate Action and the European Green Deal, available at: https://ec.europa.eu/clima/policies/eu-climate-action_en.

[59] European Parliament, 8 October 2020, Texts Adopted, P9 TA-PROV(2020)0253, available at: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/doceo/document/TA-9-2020-0253_EN.pdf

[60] D Roberts, On Climate Change, Oil and Gas Companies Have a Long Way to Go, 5 September 2020, available at: https://www.vox.com/energy-and-environment/2020/9/25/21452055/climate-change-exxon-bp-shell-total-ch....

[61] On 18 December 2020, the Modernisation Group is scheduled to hold a meeting to consider and adopt agenda for the negotiations to be held in 2021.