Efficiency in Construction Arbitration: Suggested Practical Tools

Efficiency and Cost as the Users' Concerns

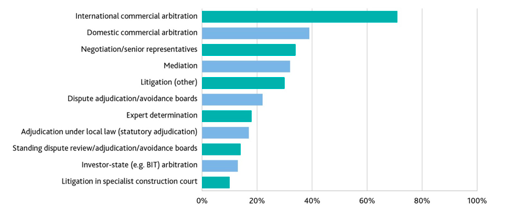

Efficiency has long been one of the main concerns of users of arbitration generally, with the cost consistently rating as the arbitration's worst feature. This is especially so in respect of construction disputes. Nevertheless, arbitration remains a strong preference among users in construction disputes. Thus, the 2019 study by Queen Mary University (London) has shown that 71% of respondents named international commercial arbitration as the most frequently used procedure of dispute resolution in construction[1]:

However, it is also seen from these statistics that arbitration is followed by negotiations, mediation, litigation, and dispute boards as means of dispute settlement. These statistics emphasize that competition to arbitration exists, and it is important that both institutions and arbitrators address the users' concerns, including that of efficiency. Thus, the same Queen Mary University study has shown that 33% of users responded that efficiency and cost influence their decision to pursue international arbitration.[2]

The need for further efficiency has also been emphasized by institutions. Unsurprisingly, the ICC Commission on Arbitration and ADR has recently updated its Report on Construction Industry Arbitrations Recommended Tools and Techniques for Effective Management.[3]

Efficiency Challenges Posed by the Nature of Construction Disputes

The higher efficiency concerns in construction arbitration are rooted in the nature of construction disputes.

Construction disputes tend to be highly complex factually. Construction projects go on for years, with very active interaction between the employers, contractors, engineers and other contract administrators, adjudicators, and designers. This produces numerous facts and extensive records, such as drawings, programmes and programmes' updates, daily, weekly and monthly reports, minutes of numerous meetings and correspondence. It also results in numerous disagreements and claims. This amount of evidence has proven to be extremely hard to manage.

On top of that, the facts and records in construction arbitrations are highly technical. As a result, the most important type of evidence in such cases is expert evidence (geological, engineering, programming and quantum being just the most typical types). The expert evidence is often so extensive and complex that the arbitrators struggle to resolve the differences cost and time-efficiently.

Finally, these features leave room for the parties' disruptive tactics. To name just a few, parties may request extensive document production or instruct their experts to dispute as many arguments of the opposing experts as possible to raise opposing party's costs.

If users' interests are to be put first, these issues have to be addressed by appropriate case management and evidentiary techniques.

Practical Tools for Increasing Efficiency

(a). Proactive Role of the Arbitral Tribunal

A lot of debate has been going on in respect of more active role of tribunals recently, especially due to emergence of the Rules on the Efficient Conduct of Proceedings in International Arbitration (known as the Prague Rules).[4] The Prague Rules suggest that tribunals are entitled and encouraged to take a proactive role in establishing the facts of the case. Apart from the matters subject to this debate, it is suggested that in construction arbitration, it is crucial for tribunals to adopt a somewhat more proactive approach than it is customary in other disputes.

Thus, although construction disputes seems to involve numerous issues at first sight, in practice, in many cases, the disputes boil down to certain narrow matters. Accordingly, when the case is transferred to the tribunal, it is extremely important that the tribunal crystallize these matters without delay. For this purpose, it is helpful for the tribunal to have the case management conference immediately and try to have the disputed matters clarified in its course.

This practice is in line with the major institutional rules, like Art. 24(1) of the ICC Arbitration Rules or Art. 14.1 of the LCIA Arbitration Rules that provide for a contact between the tribunal and the parties without delay to establish procedural matters. However, when dealing with complex matters like construction, it is helpful for the tribunal to also clarify with the parties at the earliest stage (1) the facts of the case; (2) the undisputed and disputed issues; and (3) the parties' views on how the disputed issues will be dealt with both procedurally and evidentially.

As a result, tribunals can customize the procedural timetable and procedural rules to specific disputed facts of the case. Moreover, the tribunal may be able to understand very early on which procedural steps it will need to take, e.g., appoint a tribunal-appointed expert, provide for parties' experts joint reports, schedule Site visits.

The parties, on the other hand, will be encouraged to concentrate on the material matters in their submissions.

(b).Experts' Agreements and Joint Reports

The extremely high importance of expert evidence also creates challenges for tribunals in construction cases.

In a default procedure usually adopted by tribunals, parties appoint their own experts paid by these parties. Party-appointed experts produce their reports, and these reports are submitted with the parties' submissions. However, party-appointed experts often act like "hired guns" and no more than the advocates of the parties' positions. This results in extensive differences on various technical issues. These differences are then tested through reply reports and cross-examination.

When this procedure is followed in highly technical cases, the differences between party-appointed experts are often countless. Experts may also use conflicting methodologies and data sets, which makes evaluation and comparing evidence very time-consuming both for the parties and for the tribunal. Time and cost spent to test all of these differences may be enormous, although the value of this exercise for the final award might be very modest.

To avoid this, tribunals may encourage parties to have their experts:

i. Agree on the methodologies at the earliest possible occasion, better before submitting the first expert reports;

ii. Agree on the sets of relevant data for analysis;

iii. Attempt to agree on undisputed matters;

iv. If possible, submit joint reports outlining the items of agreement and disagreement; and

v. Submit alternative opinions and calculations on "figures-as-figures" basis for different assumptions.

For instance, these techniques are possible under Art. 5(4) of the IBA Rules on the Taking of Evidence or Article 6 of CIArb Protocol for the Use of Party-Appointed Expert Witnesses in International Arbitration.

If a tribunal suggests to attempt agreement, it will be very unusual for the parties and experts to dismiss this possibility altogether. At the very least, the experts' conferences will eliminate disagreements on relevant facts and documents, as well as baseline and methodology. Ideally, as a result, the experts will narrow the issues in dispute and allow the tribunal to concentrate on these crucial matters during the hearings.

For example, in one unpublished case, there were more than six separate areas of expert evidence over disruption. Because of using the proposed techniques, the experts agreed on how to measure and quantify disruption, gave a joint presentation on their findings, and no cross-examination was needed as a result.[5] In another case under FIDIC Yellow Book contract, the party-appointed experts were able to submit joint reports and lists of disagreements on delay, disruption, prolongation cost and quantum narrowing and outlining the issues of disagreement and providing numbers as figures.[6]

Unsurprisingly, ICC Commission on Arbitration and ADR names witness conferencing as one of the technics to be considered to reduce time and cost in its Report on Controlling Time and Costs in Arbitration.[7]

(c). "Hot-tubbing" of Experts vs. Cross-Examination

Tribunals may also consider alternative technics to manage expert evidence during the hearings.

Generally, experts' opinions are tested through cross-examination by counsel, without the involvement of the opposing expert, and in a linear manner (cross-examination of one expert, followed by cross-examination of another expert). The technique is known to be efficient in fact witness questioning. However, unlike fact witnesses, technical experts testify on areas of knowledge in which, generally, neither arbitrators nor counsel are experts. The issues are also often numerous. As a result, tribunals may find it difficult to navigate through the issues when they are presented linearly (often even in different days of the hearings).

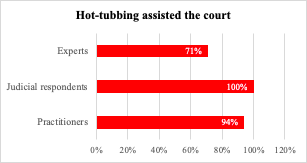

A solution to this can be found in so-called "hot-tubbing" of experts, i.e., a more informal discussion between the experts, the parties, and the tribunal, with tribunal's oversight and guidance. Hot-tubbing allows experts to engage in discussion before the tribunal, present and criticize opinions on each matter concurrently, with the tribunal asking questions to all experts in parallel. This technique allows the tribunal to resolve one technical issue after another and benefit from the experts' discussion and knowledge to a maximum extent.

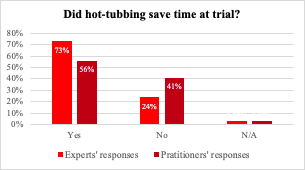

Notably, in England & Wales (where the technic has been introduced not long ago), a study by a Civil Justice Counsel has shown the following responses[8]:

Although numbers differ between experts and practitioners, it is clear that in more than 50% of cases, efficiency was perceived to increase because of hot-tubbing.

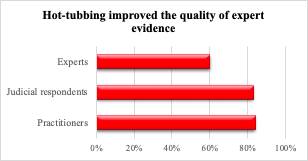

The numbers in respect of quality of evidence are even more convincing, with the vast majority of respondents noting the increased quality:

(d).Tribunal-appointed Experts

After the tribunal and the experts narrowed down the disputed issues to only the relevant ones, it may still be the case that experts have fundamental disagreements in respect of such issues. In such cases, it is worth considering whether a tribunal-appointed expert can be appointed to assist the tribunal. Many institutional rules give the tribunal this power (e.g., Art. 25(4) of the ICC Arbitration Rules; Art. 21 of the LCIA Arbitration Rules).

Needless to say that this power shall be exercised with caution to avoid a tribunal-appointed expert taking the decisive role as a "fourth arbitrator". Furthermore, involvement of tribunal-appointed experts is likely to raise costs. Therefore, the tribunal shall do a certain "cost-benefit analysis" before opting for the tribunal-appointed expert. The reasoning of a tribunal's refusal to appoint such an expert in American Bell International vs. Iran is interesting in this respect[9]:

"With regard to the necessity of experts, the Tribunal notes that the parties have had more than adequate time to prepare their case and engage their own experts. Having studied the case the Tribunal concludes that any possible benefits to be derived from the appointment of an expert are not in proportion to the delays and consequential prejudice to all parties which would ensue."

At the same time, tribunal-appointed experts have shown potency in assisting tribunal in various matters. For example, in one case, a dispute arose under a construction contract with a condition that revenue from the constructed object is shared between the parties. One of the crucial questions was the calculation of the revenue. The tribunal-appointed expert finally reached a number that was almost in the middle between the party-appointed experts' evaluations.[10] If the expert had not been appointed, the tribunal would have been faced with a difficult choice between the two conflicting approaches, none of which reflected the appropriate evaluation.

If a tribunal does find that it is appropriate to appoint an expert, it may first seek to obtain the parties agreement on the appointment, the candidates, and the terms of reference for the tribunal-appointed experts. If parties cannot agree on the expert, the tribunal may seek assistance, for example, from the ICC International Centre for ADR who can provide to the tribunal the name of one or more experts in a particular field of activity.[11]

(e). Documentary Evidence Management

As far as documents are concerned, tribunals need to be aware of the inefficiencies document production can bring to arbitration due to amount of records involved in construction projects. In this light, it is important to balance the interests of the parties in determining the scope of production and avoid standard approaches. This is also in line with the guidance given in Appendix IV to the ICC Arbitration Rules, which invites to avoid or limit document production when appropriate to control cost and time.

The relevant factor in construction arbitrations, especially the ones under FIDIC set of contracts, is that construction contracts often provide for extensive document exchange between the parties and, if present, with the contract administrator throughout the project. The contract administrator and its staff are also often present at the site. If this is the case, the parties are likely to have access to the same sets of data, and tribunals may consider limiting production only to purely internal documents (if relevant and material).

It is also noteworthy that in many cases the majority of documents are used by experts only, most common examples being daily and monthly reports used to establish critical paths and delay and cost records. Disclosing these documents through standard document production proceedings may be extremely burdensome for the parties. If this is the case, tribunals may seek agreement of the parties on common access of experts to the same sets of records.

This is also an issue to be discussed with the parties very early on in the proceedings. If managed correctly, the measure may limit the work of experts on both sides significantly and reduce the number of expert reports, cutting one of the major costs involved in construction arbitration.

Conclusions

The above are just some suggestions on techniques that can be used to increase efficiency in construction disputes. However, the more general point is that the more complex the dispute gets, the more tailored approach is appropriate to manage and resolve it. For construction cases, this means, first of all, the need for more active tribunals, early determination of disputed issues, adopting techniques to narrow these issues down and efficient management of evidence.

[1] 2019 International Arbitration Survey: International Construction Disputes, Queen Mary University of London, Pinsent Masons, p. 10; available at: http://www.arbitration.qmul.ac.uk/research/2019/.

[2] 2019 International Arbitration Survey: International Construction Disputes, Queen Mary University of London, Pinsent Masons, p. 22; available at: http://www.arbitration.qmul.ac.uk/research/2019/.

[3] Construction Industry Arbitrations – Report of the ICC Commission on Arbitration and ADR; available at: https://iccwbo.org/publication/construction-industry-arbitrations-report-icc-commission-arbitration-adr/.

[4] Available at: https://praguerules.com/prague_rules/.

[5] Douglas S. Jones, 'Party Appointed Experts in International Arbitration—Asset or Liability?', in Stavros Brekoulakis (ed), Arbitration: The International Journal of Arbitration, Mediation and Dispute Management, (© Chartered Institute of Arbitrators (CIArb); Sweet & Maxwell 2020, Volume 86 Issue 1) pp. 2 - 21, Section 9; available at: http://www.kluwerarbitration.com/document/kli-ka-amdm-86-01-002-n?q=jones%20AND%20party-appointed%20expert.

[6] 'Konoike Construction Co. Limited V. Ministry of Works, Tanzania (Final Award), 10 February, 2016', Arbitrator Intelligence Materials, (© Kluwer Law International; Kluwer Law International); available at: http://www.kluwerarbitration.com/document/kli-ka-aim-awards2019-445-n?q=Konoike%20Construction%20Co.%20Limited%20V.%20Ministry%20of%20Works%2C%20Tanzania.

[7] ICC Arbitration Commission Report on Techniques for Controlling Time and Costs in Arbitration; available at: https://iccwbo.org/publication/icc-arbitration-commission-report-on-techniques-for-controlling-time-and-costs-in-arbitration/

[8]Concurrent Expert Evidence and "Hot-Tubbing" in English Litigation since the "Jackson Reforms", Legal and Empirical Study, Civil Justice Council; available online at https://www.judiciary.uk/wp-content/uploads/2011/03/cjc-civil-litigation-review-hot-tubbing-report-20160801.pdf.

[9] American Bell International Inc. v. The Islamic Republic of Iran, the Ministry of Defense of the Islamic Republic of Iran, the Ministry of Post, Telegraph and Telephone of the Islamic Republic of Iran and the Telecommunications Company of Iran IUSCT Case No. 48.

[10] 'Danish Polish Telecommunication Group I/S v. Telekomunikacja Polska S.A. (Partial Award), 3 August 2010', Arbitrator Intelligence Materials, (© Kluwer Law International; Kluwer Law International); available at: http://www.kluwerarbitration.com/document/kli-ka-aim-awards2019-063-n?q=%27Danish%20Polish%20Telecommunication%20Group%20I%2FS%20v.%20Telekomunikacja%20Polska%20S.A.

[11] https://iccwbo.org/dispute-resolution-services/experts/proposal-experts-neutrals/

Vladimir Khvalei

Arbitration Association

Moscow