Machine Arbitrators Change the Rules of the Game

The world we are living in becomes more and more sophisticated every day. One of the reasons for that is the development of technology. 20 years ago, it was impossible to believe a person would one day be able to fly without plane or parachute, yet this day came on 14 July 2019 when the French inventor Franky Zapata flew above the crowd on his Flyboard in Paris at the military parade on the National Day.

Neural networks analyze the photos we post on Facebook and Instagram and programs paint pictures, write novels and music. All these things have become a part of our reality.

Does technology influence arbitration? Yes, definitely! Online arbitration, video-conferencing, digital databases, analysis of court and arbitration practice and document constructors are used by the parties and arbitrators on a day-to-day basis. Arbitral institutions and professional organizations are also involved in the process: the ICC issued the Commission Report on Information Technology in International Arbitration[1] and the ICCA-NYC Bar-CPR Working Group published its draft of the Cybersecurity Protocol for International Arbitration.[2]

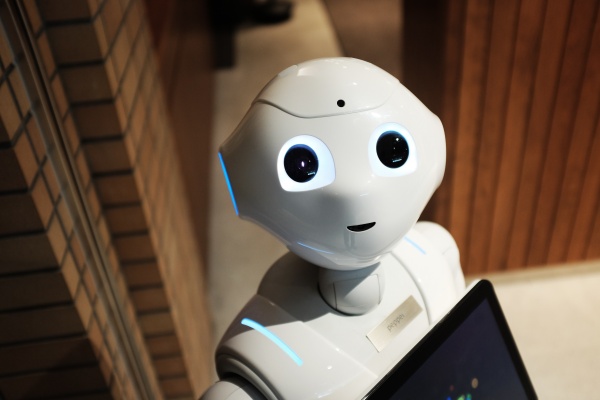

We have now reached the closest point for the discussion of the scariest arbitration, "what if": what if the technologies do not only assist arbitration but make decisions and resolve disputes in arbitration? Is it in line with the existing principles? Does it allow the parties to enjoy their rights fully? Does it require any changes to be made to the existing arbitration laws and rules? In this article we will try to review these issues.

Does "pale, male and stale" become "electronic, modern and machine"?

Currently all attempts to increase the diversity in international arbitration relate to the breaking of the "pale, male and stale" paradigm, however, the diversity almost never considers the involvement of the machine arbitrators.

Arbitration rules do not explicitly provide the possibility for the parties to choose either a human or a machine arbitrator. Some of them (for example, the UNCITRAL Arbitration Rules and the ICC Arbitration Rules) have no stipulation that the arbitrator should be human, which theoretically makes it possible for the parties to nominate a machine arbitrator. At the same time the other rules, including the VIAC Arbitration Rules (Art. 16) and the Arbitration Rules of the International Arbitration Court at the BelCCI (IAC at the BelCCI; Art. 5), set that the arbitrator should be a person (or even a natural person) in full legal capacity. The Arbitration Rules of the IAC at the BelCCI go even further, as only "capable natural person possessing appropriate professional knowledge and necessary personal qualities" can be an arbitrator. It is quite challenging to valuate the professional knowledge and personal qualities of human arbitrators, and almost impossible to do it for machine arbitrators. Such knowledge and qualities are vitally important for the cases when fairness and justice depend on human understanding of the facts and the law and when there is a place for a precedent.[3]

One of the key principles of arbitration is impartiality and independence of arbitrators. It may seem that a machine arbitrator is the most impartial and independent thing because it depends exclusively on its own algorithm and has no empathy for any of the parties.

However, if we dive deeper, the machine arbitrator is a program applying artificial intelligence and machine learning (AI and ML) mechanisms. The program goes through a learning cycle where the program is taught to make decisions based on the previous court and arbitration practice, upon the input of the developer. This means that the developer of such a machine arbitrator may influence the AI behaviour by providing relevant cases in favor of one of the parties (though in ideal world the machine arbitrator should learn itself having the access to information). In fact, this forms a kind of pre-disposition and makes such a machine arbitrator neither impartial nor independent.

If we imagine the balance is maintained while the machine arbitrator is "learning", is there a technical possibility of having such an arbitrator in general? The answer is both yes and no. There are a few programs which may be used for a resolution of the disputes, for example, SmartSettle[4] for negotiations, Ross[5] which is the first AI-lawyer doing research and generating answers with the reasoning, Legalmation[6] which generates early-phase answer to the claims within 2 minutes and Lex Machina[7] and Case Cruncher Alpha[8] which predict the potential outcomes of cases. However, currently none of these programs are universal for all types of disputes or able to replace a human arbitrator. However, some authors believe that the revolution of the AI by 2030 will have caused the "structural collapse" of law firms[9], so we need at least 10 years to know the answer.

"Black mirror": shall the arbitration clause reflect the machine arbitrator?

One may ask whether it is necessary to have the possibility of nominating the machine arbitrator in the arbitration agreement. Considering the absence of regulations for such arbitrators in different arbitration rules and guidelines, this would be a wise approach. Moreover, the arbitration agreement in this case shall determine the number of arbitrators, the interaction between human and machine arbitrators and the procedure for providing software-compliance in the case when there are two or more machine arbitrators. In addition, it might be useful to provide a reserve human arbitrator in case there are some technical issues with the machine arbitrator.

The possible arbitration agreement based on the ICC model arbitration clause and allowing machine arbitrators could be as follows:

All disputes arising out of or in connection with the present contract shall be finally settled under the Rules of Arbitration of the International Chamber of Commerce by one arbitrator appointed in accordance with said Rules. The parties may jointly nominate a machine arbitrator (the title of the program to serve as the machine arbitrator, if already agreed) and a reserve human arbitrator who should observe the arbitration proceedings and replace the machine arbitrator in case any irreparable technical problem arises. The IT point person[10] shall observe the arbitration proceedings, test and ensure the proper functioning of the machine arbitrator, and, in case any technical problem arises, eliminate this problem or establish that this problem is irreparable. The seat of arbitration shall be Paris, France. The language of arbitration shall be English.

The arbitration clause for such potential disputes should be rather detailed, setting by default some mechanism to overcome potential issues, especially at the early stages of testing of machine arbitrators in real life. Of course, the arbitration clause proposed above is not ideal, but it may be used as the basis for a more detailed regulation of the work with a definite machine arbitrator agreed upon by the parties.

"If not us, who? If not now, when?": Kompetenz-kompetenz principle and machine arbitrator.

One of the most fundamental principles of international arbitration is the competence of the tribunal to decide upon its own jurisdiction. Will it be an issue for a machine arbitrator to decide if the arbitration clause is valid, and is this particular program duly authorized by the parties to the dispute to resolve the case?

Apparently, yes, especially in the very first stages. If the issue is very simple, for example, the one related to the title of the arbitral institution, the decision may be taken by the system applying case-based reasoning and the previous practice of this institution.

However, when it goes about the scope of the disputes to be resolved by the machine arbitrator and the precise powers of this arbitrator, it might cause some difficulties. In case, when analysis of the exact wording of the arbitration clause is not enough (if there is a need to establish the intentions of the parties through their correspondence and actions), the algorithm may not cover all the shades of human intent when concluding the contract, which would make the decision on jurisdiction fair and just. Thus, the cases with complex jurisdictional issues still require the involvement of a human arbitrator.

Lex arbitri for machine arbitrators.

Another interesting issue related to the machine arbitrator is the issue of the seat of arbitration and, consequently, the issue of lex arbitri. Choosing the seat of arbitration in a "human" arbitration means choosing the law applicable to the procedure (if this law is not agreed upon by the parties). Everything is very simple when a human arbitrator comes to the seat of arbitration and renders the award there.

However, what about the machine arbitrator? If you go to the seat of arbitration with the access to interface with the machine arbitrator there, but its servers are physically hosted in another part of the world or even in the cloud, should you apply the laws of the country where the servers of the machine arbitrator are? Does it mean that the decision of such an arbitrator would always be rendered out of the seat of arbitration agreed upon by the parties?

We assume that the most reliable way to deal with this issue and to avoid any doubts is to agree upon the applicable law in the arbitration clause.

Enforce it if you can: award rendered by the machine arbitrator.

Will the decision made by the machine arbitrator contradict the public policy of the state where the award is to be enforced, in case when the national legislation of this state provides for human arbitrators? This may happen, because having a non-human arbitrator may be considered a violation of the principle of the resolution of the dispute by the appropriate court. For example, if the national legislation provides a for the resolution of the dispute by the natural person in full capacity, nominated by the parties upon their agreement or appointed in accordance with the procedure set for the resolution of the dispute (as it is provided by Art. 1 of the Law of the Republic of Belarus "On International Arbitration Court"; however, there is no such wording in the UNCITRAL Model Law), referring the case to the machine arbitrator may cause a violation of the public policy. Although these public policy issues have a very high probability of arising, they will be eliminated when the practice develops.[11]

Therefore, you need to hold the investigation of the national legislation in the country where potential enforcement may take place and check, at least, the "humanity" of arbitrators in this jurisdiction.

They will be back, or instead of conclusion.

AI in arbitration, and especially the machine arbitrators, is something that will draw our attention in the nearest future. It will challenge the existing rules and practice and challenge the arbitration practitioners all over the world, inviting all of us to develop as fast as the technology does. The only thing is required from us is to take on this adventure.

Veronika Pavlovskaya,

Associate at Arzinger & Partners (Belarus), Chief Coordinator at Young ADR – Belarus

[1] https://iccwbo.org/publication/information-technology-international-arbitration-report-icc-commission-arbitration-adr/

[2] https://www.arbitration-icca.org/media/10/43322709923070/draft_cybersecurity_protocol_final_10_april.pdf

[3] A. Panov, Machine arbitration: will we be out of our jobs in 20 years? http://arbitrationblog.practicallaw.com/machine-arbitration-will-we-be-out-of-our-jobs-in-20-years/

[5] https://rossintelligence.com/

[6] https://www.legalmation.com/

[8] https://www.case-crunch.com/

[9] Report: artificial intelligence will cause "structural collapse" of law firms by 2030

https://www.legalfutures.co.uk/latest-news/report-ai-will-transform-legal-world

[10] The term "IT point person" is provided in the Annex to the Commission Report on Information Technology in International Arbitration

[11] J. W. Nelson, Machine Arbitration and Machine Arbitrators

www.youngicca-blog.com/machine-arbitration-and-machine-arbitrators/