Notes from Swedish law day in Moscow 23 October 2018

An event addressing the substance of Swedish law was organized in Moscow by the Swedish Arbitration Association, Young Arbitrators Sweden, the Arbitration Institute of the Stockholm Chamber of Commerce and by the leading Swedish lawfirms Delphi, Hannes Snellman, Lindahl, Mannheimer Swartling, Norburg & Scherp, Roschier, Vinge and White & Case.

Sweden is recognized globally for its neutrality, transparency and consistent adherence to the rule of law. Swedish law provides a neutral, predictable and cost efficient base for dispute resolution in international trade and commerce. In particular, the choice of Swedish law has been, and continues to be, common in international contracts involving Russian parties. Over the years, a large number of Russia-related contracts have been governed by Swedish law, including major and pioneering commercial transactions.

Kaj Hobér explained that many Soviet and Russian international contracts have since long ago pointed to Swedish law as the applicable law. To his experience Swedish law is appropriate as it is pragmatic, takes into account commercial realities and is flexible. Although flexible, Swedish law is predictable. Sources of Swedish contract law are accessible also in English.

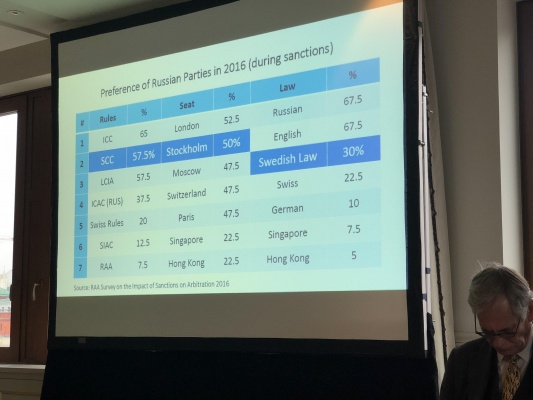

Roman Zykov has conducted an ambitious empirical study held by the Russian Arbitration Association and found that Swedish law is the third most popular choice of applicable law in Russia in international contracts, after Russian and English law. There is also statistics indicating that the Arbitration Institute of the Stockholm Chamber of Commerce is the second most frequent arbitration institute in Russian international disputes.

Alexander Komarov pointed to international contracting parties’ frequent need to refer to a third jurisdiction for the applicable law. To his opinion Swedish contract law is a suitable choice as it is a modern, reliable and user friendly alternative. It reflects the most prominent ideas of modern commercial law and appropriately addresses practical commercial problems.

Kristoffer Löf explained that Sweden is a small country highly dependent on export and its law therefore needs to be in line with international commercial practices. Sweden has experience from legal questions arising in international contracts, since there has been a long history of parties choosing Swedish law as the applicable law.

Bo GH Nilsson has represented the Russian Federation in investment arbitrations. To his experience Swedish courts and arbitrators are not negative towards Russian parties. He has been successful in Swedish courts when challenging arbitral tribunals’ jurisdiction. Kristoffer Löf echoed him and pointed to statistics regarding challenges of arbitral awards in Sweden. Challenges by Russian claimants were successful in more than 20 % of the challenges, which is extraordinary since only 10 % of the total challenges were successful. This clearly shows that there is no bias in Sweden against Russian parties.

Generally on Swedish law

Christer Söderlund presented an overview of Swedish law. The legal developments in Russia and Sweden are quite similar. Both Swedish and Russian law were historically mainly based on customary law and thereafter influenced by German law when codifying contract law. Sweden lacks a comprehensive statute on contract law. The Contract Act is old (from 1915) and addresses only some fragmentary questions. Case law provides guidance by filling the gaps in statutory law, for instance dealings with competing causating events, just to mention one of many examples when determining the quantum of damages. The Swedish Contract Act is old and Sweden has accumulated an enormous treasury of case law which clarifies and provides guidance to many conceivable matters in contract law.

The present Swedish contract law is based on the idea of liberalism and freedom of contract. Swedish contract law is in line with all the major legal systems. It is based on the principles of freedom of contract, pacta sunt servanda, loyalty and good faith. Compared to most other jurisdictions Swedish contract law is non-formalistic and openminded to arguments referring to commercially sensible solutions.

Swedish contract law is in harmony with the UNIDROIT Principles of International Commercial Contracts. Anders Reldén explained that the Swedish Supreme Court in its reasonings often refers to the UNIDROIT Principles.

In Christer Söderlund’s experience, Swedish law is well understood conceptionally by Russian lawyers. Bo GH Nilsson made a remark that English law, in contrast, is harder to understand for a civil law lawyer. Many concepts in Anglo-American, law such as consideration and estoppel, are foreign to a civil law layer. Reversely, there are no known Russian concepts that are hard to understand for a Swedish lawyer.

James Hope addressed the issue of certainty. To his opinion the common law is certain due to the many cases. Civil law, however is also certain, as it relies on general principles developed by professors. Swedish law has a good combination of case law and general principles.

Particular reflections in view of the awards in the Naftogaz-Gazprom dispute

Roman Zykov explained that the large dispute between Gazprom and Naftogaz was caused by the industrial slow-down in 2008 and the lower market prices on energy sources. The slow down prompted renegotiations of long term contracts. Many parties were able to settle their renegotiations amicably but some contracts ended up in arbitration, such as the contract between Gazprom and Naftogaz.

Mr. Zykov said that everybody knows that long term gas contracts will be affected by changed circumstances and that the contracts contain sophisticated price review mechanisms to handle changes. Arbitral tribunals are often vested with a far reaching authority to determine the prices. Such authority to make price revisions is not a traditional legal question.

Mr. Zykov furthermore explained that the actual dispute started in 2014 and concerned on the one hand Naftogaz’s obligations in relation to a take-or-pay clause and payment for used volumes in Q2 2014, and on the other hand Gazprom’s obligation to accept a price reduction, an adjustment in the price revision mechanism and to provide compensation for unused transit capacity.

The arbitral award is available, due to challenge proceedings in the Svea Appeal Court (Stockholm), but to a large extent redacted (marked in black) for reasons of confidentiality. What we know is that all Gazprom claims were rejected and that the tribunal applied Sec. 36 in the Swedish Contract Act. The arbitral tribunal’s complete reasoning with respect to Sec 36 is, however, not displayed.

Bo GH Nilsson commented on the arbitral award and explained, as far as is possible to discern from the disclosed award, that it is not a landmark or representative case. To his mind the arbitral tribunal’s reference to non-applicable competition law when applying Sec. 36 in the Swedish Contract Act may seem controversial, but the same end result could have been achieved in most other jurisdictions based on the application of other legal concepts.

Mr. Nilsson explained that the tribunal first concluded that no national or EU competition law was applicable. Then the tribunal continued to determine whether the take-or-pay provision was unconscionable according to Sec. 36 in the Swedish Contract Act. The tribunal took into account non-applicable competition law issues and concluded that the take-or-pay provision deviates from generally accepted principles of competition law and therefore is unconscionable and modified it. To Mr. Nilsson’s opinion the tribunal’s reasoning is rather unusual and the same conclusion could have been made also in jurisdictions without a statutory provision similar to Sec. 36 in the Swedish Contract Act.

Sec. 36 in the Swedish Contract Law Act regarding unconscionable contracts

Christer Söderlund stated that Sec. 36 in the Swedish Contract Act – which allows for unconscionable contracts to be modified or set aside – is a last resort argument, which is very rarely successful in practice. He does not have any personal experience from a contract being modified or set aside according to Sec. 36. He pointed to the fact that similar legal concepts are found in German, French and Russian law.

Bo GH Nilsson emphasized that Sweden adheres to the fundamental principle of pacta sunt servandaand will hold the parties to their contract. Swedish law did originally not have any statutory provision on hardship. The statutory provision was introduced in the 1970’s by the Sec. 36 in the Swedish Contract Act. It’s application is exceptional and limited to situations where the circumstances that were not foreseeable at the time of the conclusion of the contract and have entailed dramatical changes.

James Hope explained that in most jurisdiction unfair terms or terms that are affected by a change of circumstance are completely invalid. He finds the Swedish solution, according to which the term can be modifiedinstead of completely invalid, is better suited for long term contracts.

Mr. Hope described Sec. 36 in the Swedish Contract Act as a rule for exceptional cases mainly aimed at B2C-contracts. However, undue behavior during preliminary B2B negotiations – such as threat, fraud, duress – is a ground for modification or setting aside the contract.

Sec. 36 is applicable as a tool to modify limitations of liability if the breach is intentional (willful) or grossly negligent. The Swedish Supreme Court in the case NJA 2017 s. 113 upheld a limitation of liability clause in a B2C contract involving a negligent breach, thereby indicating that the possibility to modify a limitation of liability is extremely limited. Anders Reldén stated that the Supreme Court through the case has demonstrated that the unfairness test in Sec. 36 is not only dependent on gross negligence and that also other factors are relevant.

Interpretation of commercial contracts governed by Swedish law

Fredrik Ringqvist and Christina Ramberg presented an overview of the interpretation and construction of contracts under Swedish law.

The starting point for the interpretation and construction of contracts is the parties’ common intention. The wording of the contract is crucial to establish the common intention. When the wording is unclear or incomplete, the contract is construed taking many factors into account, such as the parties’ preliminary negotiations and behavior subsequent to the conclusion of the contract, party usage, general trade usage, bad faith, implied terms, and the nature and purpose of the contract.

Arguments regarding commercial sense (the nature and purpose of the contract) are often successful – provided that the argumentation is very pedagogic.

The Swedish methods regarding interpretation and construction of contracts is in line with the UNIDROIT Principles of International Commercial Contracts and to (modern) English case law.

Remedies for breach of contract under Swedish law

Rikard Wikström-Hermansen and James Hope presented an overview of the remedies for breach of contracts under Swedish law.

The parties are free to contract as to which remedies shall apply and to what extent.

A party is generally allowed to withhold its performance when the counter party breaches the contract or such a breach is anticipated. The withholding must be proportionate to the breach (or proportionate to the anticipatory breach).

Specific performance, i.e. the obligation to perform what the contract stipulates, is a main remedy in Swedish law – as in all civil law jurisdictions. By contrast, damages is the main remedy in Anglo-American law. Cure and replacement are examples of specific performance. Specific performance is not available if it would be unreasonably burdensome. A claim for specific performance can be combined with a claim for damages.

Price reduction (actio quanti minoris) is a generally available remedy in most types of contracts. The Swedish Supreme Court has stated that the aim of price reduction is to restore the balance between the parties. A claim for price reduction can be combined with a claim for damages.

Damage is a generally available remedy. Damages cover full compensation, including compensation for loss of profit. The formula to determine the quantum of damages is that the party not in breach should be put in the same financial situation as if the contract had not been breached. Swedish law has a foreseeability test (adequate causality).

Swedish law accepts liquidated damages, as long as the liquidated damage at the time of conclusion of the contract is not obviously intended as a penalty (i.e. a compensation intended to provide compensation in excess of the injured party’s conceivable future loss).

Parties are advised to expressly state in their contract to what extent an injured party can claim additional damage for loss exceeding the liquidated damages, by for instance stating that liquidated damages is a sole remedy.

Termination for breach of contract (termination for cause) is allowed, provided that the breach is fundamental (material). Notice of termination is risky, as an unjustified termination is a breach in itself. Termination for breach of contract can be combined with a claim for damages. It is possible to agree on the exclusion of the right to terminate, which is quite common in M&A contracts.

Swedish default law has comparatively harsh rules on notice of breach of contract and notice of claims for remedies. The notice periods are short and the reasons for the notice should be clearly expressed.

The parties are free to limit their liability and obligations with respect to various remedies. Contractual limitations are upheld, accepted an enforceable (see above regarding Sec. 36 in the Swedish Contract Act on unconscionable contracts).

Swedish law on remedies for breach provides a flexible and commercially-oriented approach.

Christina Ramberg

Roman Zykov

Arbitration Association

Moscow