Resolution of the Plenary Session of the Russian Supreme Court on Arbitration: 10 takeaways

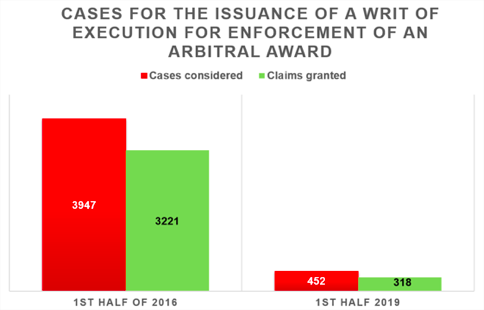

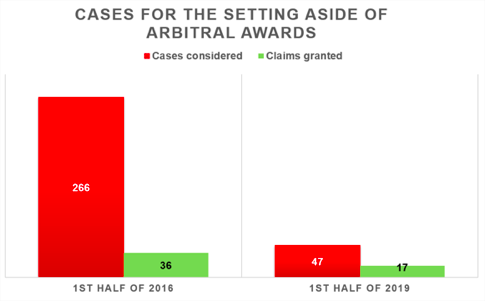

On 10 December 2019 the Plenary Session of the Russian Supreme Court passed Resolution No. 53 "On the carrying out of functions by courts of the Russian Federation regarding the assistance and monitoring of arbitration proceedings and international commercial arbitration" (hereinafter, the "Plenary Session Resolution"). In view of the fact that the Supreme Court sometimes takes an inconsistent position on arbitration, the Plenary Session Resolution turned out to be much better than expected. However, despite all the friendliness of the Plenary Session Resolution toward arbitration, it is unlikely to improve the situation with arbitration in Russia, since the main obstacle to it development is the administrative barrier in the form of the requirement to obtain a permit from the Russian Ministry of Justice, which no Russian arbitral institution has been able to overcome within a purely legal framework. As a result of the reforms, the arbitration market shrank nearly tenfold.

Nevertheless, the author has attempted to summarize the most interesting provisions of the Plenary Session Resolution.

1. Assistance is sort of being provided to arbitration courts, only arbitration courts sort of don't exist...

The Plenary Session Resolution once again provided a reminder that state courts should provide arbitration courts with assistance in the appointment, disqualification, or termination of powers of an arbitrator along with the obtainment of evidence and the adoption of interim measures.

However, in the post-reform practice of Russian state courts, only ten cases were found in which the parties asked state courts for assistance in the appointment of arbitrators and all these cases were related to the arbitration courts with controversial reputation. The assistance was granted only in 5 cases, and these cases were backed to 2017.

Similarly, there are practically no statistics for cases in which the parties attempted to obtain evidence with the help of state courts for use in arbitral proceedings. In the small number of cases (a total of two) where the arbitral tribunals, acting under the Rules of the Arbitration Center at the RSPP [Russian Union of Industrialists and Entrepreneurs], approached a state court for similar assistance, this assistance was denied.[1]

To conclude, in theory the state courts are prepared to provide assistance to arbitral tribunals, but there are almost no arbitration courts that we of need of such assistance...

2. The Kiev Agreement does not apply to arbitration courts

The main objective of the Agreement On The Procedure For Resolving Disputes In Connection With Business Activities that was signed on 20 March 1992 in Kiev (the "Kiev Agreement") was to fill the vacuum that arose after the breakup of the USSR in 1991. This led to the need to create a legal mechanism for determining the jurisdiction in commercial disputes within the CIS, and for the enforcement of judgments handed down by state courts of one CIS country in the other CIS country. Thus, the Kiev Agreement was mainly intended to regulate proceedings in state courts, not in arbitration. However, insofar as at that time the majority of CIS countries were not parties to the New York Convention (except for Russia, Belarus and Ukraine), the Kiev Agreement also applied to arbitral awards. But after most of the CIS countries joined the New York Convention, the existence of a double enforcement regime (under the Kiev Agreement and the New York Convention) began to create problems in practice.

In order to avoid such collision, the Supreme Arbitrazh [Commercial] Court of the Russian Federation as far back as 1996 explained that the Kiev Agreement does not apply to arbitral awards,[2] however, state courts still continued to rely on it.[3] In December 2018, the Russian Supreme Court in its Overview of Court Practice[4]again pointed out that the provisions of the Kiev Agreement applied only to issues of mutual recognition and enforcement of judgments handed down by courts of foreign countries, and not arbitration courts. Nevertheless, even after this explanation, courts continued to invoke the Kiev Agreement in cases involving the recognition and enforcement of foreign arbitral awards, including with respect of serving the respondents in arbitration.[5]

In order to terminate this practice, the Plenary Session Resolution again explained to lower courts [6] that the provisions of the Kiev Agreement and the Minsk Convention [7] do not govern issues of the recognition and enforcement of foreign arbitral awards.

3. The procedure for sending notifications, established for the hearing of cases in state courts, does not apply to arbitration

Similarly, the Plenary Session Resolution once again explained the obvious, [8] namely that "by virtue of the dispositive arbitration proceedings, the parties are entitled to establish any procedure for receiving written communications or to follow the procedure set forth in the rules of a permanent arbitration institution whose application the parties agreed to."

4. The place of arbitration is not the same as the location of the arbitral institution or the hearing venue

Insofar as for a long time the only example of an arbitration court in Russia was the International Commercial Arbitration Court at the Chamber of Commerce and Industry of the Russian Federation (the “ICAC”), judges gathered information on arbitral proceedings based on the procedural traditions of the ICAC. These traditions included holding hearings at the location of the ICAC, thanks to which the place of arbitration, location of the arbitral institution and the hearings venue always coincided.

Therefore, when judges came up against some "suspicious arbitrations" where the hearing was held in a place other than place of arbitration or the location of an arbitral institution, they viewed it as a violation of the arbitration agreement.

For example, in 2001 Russian state courts refused to recognize and enforce an arbitral award of the Arbitration Institute at the Stockholm Chamber of Commerce, finding a violation of the arbitration procedure agreed by the parties, because the tribunal held the hearing in Stockholm, while the place of arbitration was Moscow. [9]

In the famous "Singapore Arbitration Case" the courts found that the hearing of the notorious Russia-Singapore Arbitration Center took place in Moscow, and the award was actually signed in Moscow, therefore the courts should apply the procedure for enforcing Russian domestic awards, and not foreign.[10]

Therefore, in order to avoid further misunderstandings in this matter, the Plenary Session Resolution states: "The place of arbitration does not have to be the same as the location of the arbitral institution under whose rules the arbitration proceedings are held, or the venue of the hearing in the case."

5. Alternative and asymmetrical arbitration clauses

The Sony Ericsson case attracted a lot of attention. [11] In this case, arbitrazh (state commercial) courts found invalid a dispute resolution clause, because it provided only one party with the ability to choose whether to apply to a state court or to the ICC. Thus, this clause was not only alternative, but also asymmetrical, which, in the opinion of the courts, violated the procedural equality of the parties. The decision of the Supreme Arbitrazh [Commercial] Court in this case [12] left many questions, insofar as from its text it was unclear whether the entire clause was invalid, or only that part which granted additional procedural rights to one party in comparison to the other party.

This lack of clarity seriously rattled the arbitration community, as similar alternative and asymmetrical arbitration clauses are commonly used by English banks: under such clauses, a bank has the right to choose, at its own discretion, either LCIA arbitration or a state court, while a borrower only has the right to apply to the LCIA.

In order to avoid further doubts about this, the Plenary Session Resolution states: "A dispute resolution agreement that secures the right of only one party to choose (an asymmetrical agreement), is invalid to the extent that it deprives the other party of the right to choose between the same means of resolving a dispute. In this case, each party to an agreement has the right to use any means of dispute resolution among those stipulated in the alternative agreement concluded by the parties." [13]

6. The failure to challenge before a state court a partial award on jurisdiction does not prevent to challenge jurisdiction at the stage of setting aside of an arbitral award or at the stage of enforcement

The Russian arbitration law allows to separately challenge a positive decision of an arbitral tribunal on jurisdiction, and sets a deadline for such an appeal. [14] Thus, a question has arisen: was the party obliged to challenge the award on jurisdiction, or it is a right, and such party could challenge jurisdiction after the final award is issued?

The Plenary Session Resolution explained that applying to a court for the challenge of a partial award on jurisdiction is a right, and not an obligation of the parties. [15]

7. Interim measures in support of arbitration proceedings

Despite the fact that some authors of the arbitration reform stated that Russian arbitration law has been brought into line with the 2006 UNCITRAL Model Law, this is not correct. The key changes in the UNCITRAL Model Law in 2006 concerned the enforcement by state courts of arbitral tribunals orders on interim measures as well as oral form of arbitration agreements.

Russian law, instead of introducing rules on the enforcement by state courts of decisions by arbitral tribunals on interim measures, was limited to a declarative statement that such decisions were subject to performance by the parties.[16]

Following this rule, the Plenary Session Resolution stresses that no writs of execution are to be issued for the enforcement of arbitral tribunals' decisions on interim measures. Rather, a party in an arbitration proceeding that seeks to obtain an interim measure must apply to a state court in accordance with a standard procedure.

8. A final arbitral award may not be challenged at all, if prohibited by the direct agreement of the parties. Well, almost not at all.

Following modern trends,[17] Russian legislators stipulated that arbitral awards may not be challenged when there is an direct agreement between the parties. However, the effectiveness of this provision has caused skepticism among pessimists. And for a good reason. The Plenary Session Resolution states: "Other parties whose rights and obligations were the subject of the arbitral award, and in certain cases stipulated by law, the prosecutor (part 1 of Article 418 of the Civil Procedure Code of the Russian Federation, and parts 2, 3, and 5 of Article 230 of the Arbitrazh Procedure code of the Russian Federation) has the right to challenge such a decision in court by filing an application for the setting aside thereof." [18]

The existence of such a loophole paves the way for some companies to set aside arbitral awards in cases where the parties have agreed to prohibit the challenge thereof.

9. A state court does not have the right to review an arbitral award on the merits. In theory, of course.

The Plenary Session Resolution once again confirmed what should have been understood without additional explanation: "... when resolving an application for the challenge of an arbitral award, for the enforcement thereof, a court does not have the right to reevaluate the circumstances established by the arbitral tribunal, or to review the arbitral award on the merits, and shall be limited to establishing whether grounds exist for the setting aside of the arbitral award."

As the saying goes, if only the words of the Plenary Session may reach the judges' ears. Because despite the prohibition on reviewing an arbitral award on the merits, this is exactly the sin that courts periodically commit.

The latest example is the case of the setting aside of an arbitral award issued under the ICAC Rules in 2019, when the courts held[19] that the amount of penalties awarded by arbitrators was excessive, although it was fully in line with the contract. The courts also shamelessly disagreed with the assessment of evidence in the ICAC case, although as a matter of principle they should not have reevaluated the evidence. And they did not even leave in force the part of the ICAC award that did not concern the penalties, as the Plenary Session Resolution requires, when stating that if only part of an award is invalidated, then only that part should be set aside.[20]

It is interesting that literally one month before passing the Plenary Session Resolution, the Supreme Court refused to review a court decision in this case.

10. Non-conformity with arbitration procedure or legislation must be substantial

An important innovation of the Plenary Session Resolution is the fact that the Supreme Court indicated that not every violation of arbitration procedure or the law constitutes grounds for the setting aside of an arbitral award, or for a refusal to enforce it; only substantial ones, that is, "if the violation committed led to a substantial violation of the rights of one of the parties, causing an infringement of the right to a fair consideration of the dispute." [21] Also, the party must have filed objections against such non-conformity without an unjustifiable delay, as stipulated in Article 4 of the RF Law on International Commercial Arbitration.

This provision should help prevent the setting aside of awards on formal grounds, when a violation of procedure in arbitration proceedings has in fact taken place but such violation is not substantial.

[1] Ruling of the Arbitrazh Court of the City of Moscow dated 25 October 2018 in case No. А40-221117/18-68-1727; Ruling of the Arbitrazh Court of the City of Moscow dated 13 September 2018 in case No. А40-183144/18-83-998.

[2] Letter of the Supreme Arbitrazh Court of the Russian Federation No. ОМ-37 dated 01.03.1996

[3] Ruling of the Judicial Panel on Economic Disputes of the Russian Supreme Court dated 22.10.2015 N 310-ES15-4266 in case N А36-5174/2013; Ruling of the Arbitrazh Court of the Western Siberian District dated 06.10.2017 N F04-3867/2017 in case N А03-3509/2017, Ruling of the Arbitrazh Court of the Moscow District dated 16.03.2018 N F05-2232/2018 in case N А40-204190/17.

[4] “Overview of court practice in cases involving the performance of the function of assistance and monitoring of arbitral tribunals and international commercial arbitration” (ratified by the Presidium of the Russian Supreme Court on 26.12.2018).

[5] Resolution of the Arbitrazh Court of Moscow Circuit dated 18.11.2019 No. F05-19912/2018 in case N А40-90601/2019.

[6] However, one doubts the legality of such an interpretation of the provisions of the Kiev Agreement. It would be more correct to invoke Clause 1 of Article VII of the New York Convention, which points out that the provisions of the convention do not affect the validity of other multilateral or bilateral agreements with respect to the recognition and enforcement of arbitral awards. This very article says that notwithstanding the provisions of the New York Convention, a party has the right to use any arbitral award, including to the extent allowed by law or by international treaties of countries where the recognition and enforcement of such arbitral award is requested. Due to this, it has become established practice in the world that in cases where several international treaties exist which provide for the enforcement of foreign arbitral awards, priority should be given to the treaty that stipulates the most favorable conditions for the validity of the arbitration agreement or the recognition and enforcement of foreign arbitral awards.

[7] Convention on legal assistance and legal relationships in civil, family and criminal cases, dated 22.01.1993.

[8] Clause 48 of the Resolution of the Plenary Session of the Russian Supreme Court No. 53 “On the carrying out of functions by courts of the Russian Federation regarding the assistance and monitoring of arbitration proceedings and international commercial arbitration”.

[9] See Ruling of the Russian Supreme Court N 5-G01-142 dated 09.11.2001.

[10] See Resolution of the Arbitrazh Court of the Moscow District in Case No. А40-219464/16 dated 19 July 2017.

[11] See Legislation and Practice of International Arbitration in the Russian Federation (chapter authors V.V. Khvalei, I.V. Varyushina) // Baker McKenzie Yearbook on international arbitration for 2012-2013, JurisNet, pp. 370-373.

[12] Resolution of the Supreme Arbitrazh Court of the Russian Federation in case VAS-1831/12 dated 19 June 2012.

[13] See Clause 24 of the Resolution of the Plenary Session of the Russian Supreme Court No. 53 “On the carrying out of functions by courts of the Russian Federation regarding the assistance and monitoring of arbitration proceedings and international commercial arbitration”.

[14] See Article 16 of Law of the Russian Federation N 5338-1 dated 07.07.1993 “On international commercial arbitration”; Article 16 of Federal Law N 382-FZ dated 29.12.2015 “On arbitration (arbitration proceedings) in the Russian Federation”; Article 235 of the Arbitrazh Procedure Code of the RF. In accordance with the above provisions, in the wording in effect at the time of publication, this period is 1 month as from the date of receipt of the notice on the decision.

[15] See Clause 33 of the Resolution of the Plenary Session of the Russian Supreme Court No. 53 “On the carrying out of functions by courts of the Russian Federation regarding the assistance and monitoring of arbitration proceedings and international commercial arbitration”.

[16] See Clause 1, Article 17 of Law of the Russian Federation N 5338-1 dated 07.07.1993 “On international commercial arbitration”; Federal Law N 382-FZ dated 29.12.2015 “On arbitration (arbitration proceedings) in the Russian Federation”.

[17] Article 1522 of the Civil Procedure Code of France; Article 192 of the Private International Law Act of Switzerland; section 51 of the Sweden Arbitration Act.

[18] Clause 43 of the Resolution of the Plenary Session of the Russian Supreme Court No. 53 “On the carrying out of functions by courts of the Russian Federation regarding the assistance and monitoring of arbitration proceedings and international commercial arbitration”.

[19] See the case file at: http://kad.arbitr.ru/Card/eb263ec6-b232-4101-ac66-9dead6d09a8b

[20] Clause 52 of the Resolution of the Plenary Session of the Russian Supreme Court No. 53 “On the carrying out of functions by courts of the Russian Federation regarding the assistance and monitoring of arbitration proceedings and international commercial arbitration”.

[21] Clause 49 of the Resolution of the Plenary Session of the Russian Supreme Court No. 53 “On the carrying out of functions by courts of the Russian Federation regarding the assistance and monitoring of arbitration proceedings and international commercial arbitration”.

Vladimir Khvalei

Arbitration Association

Moscow