Where China meets France: some examples of the role of french courts in arbitration with a chinese element

The expanding Chinese economy and emerging cross-border opportunities make of the Chinese parties frequent users of international arbitration (I). The arbitrations with a Chinese element are not unfamiliar to French courts. While the parties’ nationality is not a source of differentiation before French courts, it might give rise to specific concerns at various stages of the courts’ intervention (II).

I. Introduction: ICC Statistics

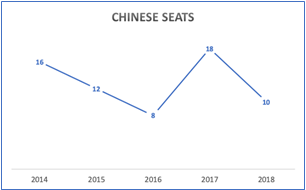

As reported2 by the International Court of Arbitration of the International Chamber of Commerce (“ICC”) headquartered in Paris, China has always held in ICC arbitrations a position of the most frequent nationality of the Asia Pacific region. This record was maintained even though the presence of parties from Mainland China slightly decreased within the last five years.3

The majority of Chinese parties act as respondents in arbitration proceedings.4

In comparison with the large number of parties within the past five years, the number of Chinese arbitrators in ICC proceedings is in average 10 times lower than the number of the parties. The majority of Chinese arbitrators act as co-arbitrators.

As for the Chinese arbitration seats, Hong Kong has been the only seat in China for the last five years, with the exception of one case (out of 64) where the arbitration was seated in Beijing.

With respect to the applicable law, the ICC Annual Reports does not give the numbers. However, while in 2014 Hong Kong law was chosen almost three times more often than the law of Mainland China, in 2015 and 2016 the laws of the Mainland were chosen almost as often as those of Hong Kong.

Finally, to finish this brief overview of ICC’s implication in arbitrations with a Chinese element, it is worth mentioning that in 2018 the ICC Court established its Belt and Road Commission to promote ICC under China’s Belt and Road Initiative.5 That development seems to be capable of attracting a significant number of arbitrations with a Chinese element in the nearest future.

II. Arbitration with a Chinese element before French courts

Arbitration agreement concluded with the Chinese parties

Not surprisingly, French courts reject their jurisdiction where there is an arbitration agreement and a party invokes a jurisdictional plea. Accordingly, if a Chinese party does not participate in the court proceedings brought by a French party in the presence of an arbitration agreement (and therefore cannot raise a jurisdictional plea), the State courts judges cannot dismiss their jurisdiction themselves.6

Interim relief before French courts in support of arbitration in China and in France

The interim relief procedures opposing Chinese parties do not imply any particularities in comparison with the proceedings involving any other parties.

In one case,7 French courts refused to grant a provisional continuation of a contract.

The case concerned a contract signed before a French party and a Chinese party, providing for arbitration under the auspices of the Hong Kong International Arbitration Centre.

The Chinese party notified to the French one its intention not to renew the contract after its expiration. The French company brought interim relief court proceedings. The relief it claimed for included the continuation of the contractual relationship till the decision on the merits and the respect of the contractual terms.

The Court ordered the Chinese party to comply with its contractual obligations till the expiration date, however, it refused to order the continuation of the contractual relationship after that date.

In another case,8 French courts granted an interim relief upon the request of a Chinese party where its partner did not pay the invoices amounting to 1,8 million dollars.

The contract provided for ICC arbitration in Paris. The Chinese party filed suit in French courts to obtain a provisional payment, the request was granted. The Court noted that the provisional payment was possible only if urgent. In the case at stake, the urgency was proven by the high amount in dispute established by the unpaid invoices and financial difficulties of the Chinese company.

Proper service of the judicial documents to the Chinese parties

The service of the judicial documents to the Chinese parties, as to all other parties established outside of the European Union, must proceed in accordance with the diplomatic rules provided for by the Convention on the Service Abroad of Judicial and Extrajudicial Documents in Civil or Commercial Matters from 1965 (“Hague Convention”). The absence of the proper service leads to a number of problems before French courts.

In one case,9 French courts concluded that in the absence of the proper service, the penalty attached to the award had not started to run.

In that case, the execution of an arbitral award rendered by a Paris-seated ICC tribunal against a Chinese party was subject to a penalty running from the thirtieth day after the receipt of the exequatur. The award received exequatur in France.

An Italian winning party brought court proceedings against the Chinese party to make it pay the penalty.

The Court first asserted its jurisdiction (opposing to the jurisdiction of the arbitral tribunal) over the penalties attached to the arbitral award. However, it rejected the request.

The Italian party argued that a French lawyer of the Chinese company was legitimate to receive the exequatur on its behalf. The Court rejected the argument as the lawyer was only empowered to conduct arbitration while enforcement proceedings and the post-award penalty was above his/her mandate. Therefore, following the Hague Convention rules, the Chinese company must have been notified in China.

Another court reached the same conclusion.10

A French company was ordered to pay by an arbitral award rendered under the auspices of the CIETAC that received exequatur in France. The French company then went bankrupt. The Chinese winning party brought court proceedings against the English and Chinese companies affiliated to the bankrupt French company for not having paid the debt under the arbitral award. The first instance court granted the request. The defendants appealed.

The Court of Appeal quashed the decision with respect to the affiliated Chinese companies as the Chinese company was obliged to follow the service rules under the Hague Convention.

The Chinese company indeed applied to the competent Chinese authorities to have them deliver a notification certificate under the Hague Convention. However, the Chinese authorities did not do that before the first instance judgement and the Chinese company did not undertake other possible measures to obtain it.

The Hague Convention service rules also apply in relation to Taiwan parties, even though France does not recognise Taiwan as an independent State.11

Annulment proceedings

Among the published decisions, none treated any particularities of the arbitrations with a Chinese element. Therefore, this section will focus on one decision of a corruption saga having given rise to multiple decisions of French criminal and civil courts.12

Under a contract, dated 31 August 1991, China Shipbuilding Corporation (later replaced by Taiwan represented by the Republic of China Navy) was to buy six ships from Thomson CSF (later replaced by Thalès). The contract contained an ICC arbitration clause. It also provided that no commission must be paid to any intermediary agent. In case it happens, the buyer could terminate the contract or get a price reduction.

Considering that such commission was paid, Taiwan initiated arbitration proceedings to obtain a price reduction and damages.

By a final award, the tribunal ordered Thalès to pay. Thalès moved to annul the award.

First, Thalès contended that the tribunal violated the international public order and breached the adversarial principle by relying on the exhibits protected by the defence secrecy.

The Court rejected the argument.

Part of the contested documents were stricken out of the record by the tribunal once the French criminal judges (in the parallel ongoing criminal investigation) informed it about the nature of the documents. The arbitrators are free in the assessment of the admissibility of evidence. Therefore, the fact that the documents protected by defence secrecy were in possession of the arbitrators for some time did not impact the validity of the award, as the tribunal did not refer to these documents in the award.

Other documents (bank account details) that were accepted by the tribunal come from the mutual legal assistance procedure granted by the Swiss judicial authorities (the sums paid for the ships were held on the bank accounts in Switzerland). Their production did not violate the international public order.

Thalès could have contested the content of those documents without disclosing the defence secrecy. However, it did not do so. Therefore, in absence of any objections, the tribunal without breaching the adversarial principle legitimately concluded that the Thalès owed the claimed sums to Taiwan.

Secondly, Thalès argued that the tribunal breached the international public policy and its mandate by allowing Taiwan to get a double compensation. It pretended that China had requested the same amounts before the arbitral tribunal and the Swiss authorities.

The Court dismissed the argument after having outlined that the arbitral tribunal had examined the argument and had expressly rejected it.

The Court rejected the motion accordingly.

Enforcement of the awards rendered in China

Enforcement procedures before French courts know some specificities in relation to the Chinese parties. Such particularities are also applicable to the annulment proceedings.

For example, French courts may refuse recognition and enforcement of an award if, following the badly drafted multi-tier clause, the tribunal rendering the award appears to lack jurisdiction.

That exactly what happened in a case of an award rendered under the auspices of the CIETAC.13

In that case, a French company and a Chinese company concluded a contract. The contract contained a dispute resolution clause. The clause, in its English version, provided that the disputes, if they could not be settled amicably, must be submitted to the CIETAC “to conduct mediation and arbitration” and that if it was “impossible to reach an agreement”, all disputes would be “finally settled in accordance with the conciliation and arbitration rules of the ICC”. The Chinese version of the clause stipulated that the disputes, after the amicable settlement failure, must be submitted to the CIETAC and may be submitted, with further agreement of the parties, to the ICC.

The Chinese company engaged arbitration proceedings before the CIETAC. An award was rendered in Beijing, favouring the Chinese party. The Paris High Court granted exequatur. The French company appealed.

The French company raised jurisdictional and international public policy pleas arguing that the parties’ agreement entrusted the mediation to the CIETAC and, in case of failure, provided for ICC arbitration in Paris.

The Court stated the rules of contract terms interpretation.

Firstly, where there is doubt about the meaning of a contract term, an interpretation should be preferred that makes the contract effective (the “effet utile” principle).

Secondly, all the contract terms are to be interpreted in consideration of other clauses and the purpose of the contract.

Applying those rules to the dispute, the Court concluded that the indication in the Chinese version of the dispute could be submitted to the ICC for arbitration. Further agreement of the parties undermined the effectiveness of the clause.

It inferred that the parties had agreed to have their disputes definitively settled by arbitration in Paris under the aegis of the ICC. Therefore, they could not simultaneously provide for the CIETAC to be used for the same purpose. Consequently, the only interpretation of the CIETAC’s role compatible with the general economy of the clause is the one of mediator who was to intervene after a failure of the amicable settlement attempt.

The Court concluded that the disputed award was made by an arbitral tribunal not designated by the arbitration agreement. The order granting the exequatur was therefore overturned.

In another case,14 French courts confirmed the exequatur over another award rendered under the auspices of the CIETAC. A French party invoked several very specific grounds against a Chinese winning party that are worth noticing.

For example, it first complained about an irregularly constituted tribunal. The arbitral tribunal was composed solely of Chinese arbitrators. The French company pretended that it had not had sufficient time to nominate an arbitrator (the CIETAC appointed an arbitrator on its behalf) and could not choose an arbitrator outside the official CIETAC list.

The Court rejected the argument considering that, according to the CIETAC’s arbitration rules, agreed upon by the parties, the French company had twenty days to nominate an arbitrator but failed to do so. An arbitrator of Chinese nationality was appointed by the CIETAC on its behalf. Moreover, during the arbitration proceeding, the French party never contested the constitution of the tribunal.

The French party also contended that the arbitral tribunal failed to comply with its mandate. In particular, the arbitral tribunal did not forward its request for the appointment of an expert to the CIETAC, whereas the arbitrators do not have the power, under the Chinese Arbitration Law, to order provisional or investigative measures.

The Court rejected the plea, considering that the CIETAC Rules provided for the referral of all matters concerning provisional or protective measures to the Chinese courts by the CIETAC, but reserved the right for the arbitrators to take all investigative measures, including the appointment of an expert. Once again, the French party never criticised the appointment of the expert during the arbitration.

The French company then invoked the adversarial principle. It argued that the time limits imposed by the CIETAC arbitration rules prevented it from nominating an arbitrator and preparing its defence in an appropriate manner. The party was also forced to request additional time limits as the use of the Chinese as the language of proceedings required translation.

The Court equally rejected the plea. As regards to the language of the proceedings, the French company accepted the CIETAC arbitration rules that provided that the proceedings were to be conducted in Chinese, in the absence of agreement between the parties in this respect. The parties did not reach any specific agreement as to the language of the arbitration proceedings.

Finally, the French company relied on the violation of the international public policy. Were invoked, inter alia, the conditions of the arbitrator’s appointment on behalf of the French company coupled with the extremely short deadlines (aggravated by the translation difficulties) that allegedly did not allow it to fully present its claims.

The Court dismissed the argument, considering that the French party criticised the merits of the award, which was forbidden before the enforcement judge.

Conclusion

While French courts treat all parties equally, some particularities relating to the Chinese element may be worth considering. Those are mostly linked to the service of the judicial documents abroad and peculiarities of Chinese language as the language of the contract or as the language of the arbitration proceedings.

Ekaterina Grivnova1

1 The author thanks Elliot Bramham for his valuable help with the article.

2 All numbers are collected from the official ICC Annual Reports for respective years (2014-2018).

3 The statistics for China include Hong Kong.

4 This and the following graphics do not include the statistics for Chinese Taipei.

5 China’s Belt and Road Initiative is a global development strategy for China adopted by the Chinese government involving infrastructure development and investments all over the globe.

6 Paris Court of Appeal, Pôle 1, ch. 1, 30 January 2018, Innovations Marketing & Development Europe – Imde (France) v. Shoxing Kady S. & Leisure Products Co Ltd (China), no. 16/25106.

7 Paris Court of Appeal, Pôle 1, ch. 8, 22 June 2018, Ash Distributions (France) v. Ash Limited (Hong Kong, China), no. 18/04463.

8 Toulouse Court of Appeal, 30 April 2018, Airbus (France) v. Asian Sky Group (Hong Kong, China), no. 17/03754.

9 Paris Court of Appeal, 18 April 2019, Cheng Long (China) v. Monsieur A. X. (Italie), no. 18/02905.

10 Versailles Court of Appeal, ch. 12, sect. 1, 8 February 2007, Sinochem Europe Holdings (Grande Gretagne) v. Monsieur Y.S. (China), Sinochem Corporation (China), Internationale D’imports Exports Zhong Yuan (China), no. 06/00716.

11 Paris Court of Appeal, Pôle 1 ch. 2, 30 March 2011, Strategic Technologies (Singapour) v. Procurement Bureau of the Republic of China Ministry of National Defence - Taiwan and Public Prosecutor (Taiwan), no. 10/18825.

12 Paris Court of Appeal, Pôle 1, ch. 1, 9 June 2011, Thales and Thales Underwater Systems (France) v. Taiwan, no. 10/11853.

13 Cour de cassation, civ. 1, 28 March 2012, M. Michel Jun (Séribo’s liquidator) (France) v. Hainan Yangpu Xindadao Industrial Co Ltd (China), no. 11-10347; Paris Court of Appeal, Pôle 1, ch. 1, 6 January 2015, M. Michel Jun (Séribo’s liquidator) (France) v. Hainan Yangpu Xindadao Industrial Co Ltd (China), no. 14/05327.

14 Paris Court of Appeal, Pôle 1, ch. 1, 31 January 2008, Thimonnier (France) v. Inner Mongolia Yili Industrial Group Co. Ltd, Hohhot, Inner Mongolia (China), no. 06/15363.

Ekaterina Grivnova

Paris baby arbitration

Paris