UNCITRAL and ISDS reform: Has the system of investor-state arbitration gone wrong and is there a way to fix it?

At its 50thsession (3-21 July 2017), UNCITRAL granted its Working Group III (WG III) a mandate to: (i) identify and consider concerns regarding ISDS (Investor state dispute settlement); (ii) consider whether reform was desirable in light of any identified concerns; and (iii) if the Working Group were to conclude that reform was desirable, develop any relevant solutions to be recommended to the Commission.

The discussion of this topic started during the UNCITRAL 2016 session. At that session, UNCITRAL considered a report by the Geneva Center for International Dispute Settlement (CIDS), which suggested a road map for the possible reform of ISDS, including the potential of using the opt-in mechanism of the Mauritius Convention as a model for reform.

During its third session inVienna from 29 October to 2 November 2018, UNCITRAL Working Group III decided that multilateral reform is desirable to address various concerns regarding ISDS.

What’s wrong with ISDS?

The reform of ISDS is motivated by the need to rebalance investor and state rights and by the need to address numerous procedural and legitimacy deficiencies of investment arbitration, criticized by states and other stakeholders. The agenda for reform within UNCITRAL is largely framed by the concerns that Working Group III had identified in its sessions[1]:

1. Concerns pertaining to consistency, coherence, predictability and correctness of arbitral decisions by ISDS tribunals

The number of states and institutions suggests that ISDS contradicts the principles of equality under the law between foreign and domestic investors; fails to protect the rights and interests of nonparties; lacks transparency; and allows legal and factual incorrectness of awards and inconsistent and broad interpretations of the law.

Some states even reported experiencing investment treaties with similar provisions being interpreted differently by tribunals, including in concurrent proceedings in which the facts, parties, treaty provisions and applicable arbitration rules were identical[2].

Due to these issues, states lost trust in the ISDS process and legitimacy of specific awards. In turn, broad interpretations reduce the possibility of a state to regulate in the interests of the general public (e.g., protection of human rights and the environment) or through legitimate domestic processes.

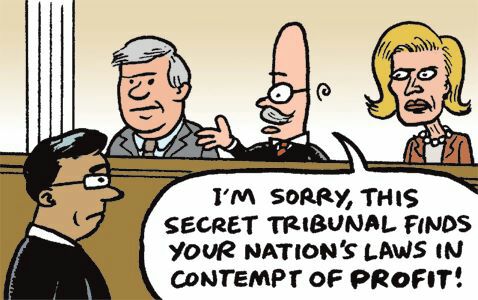

Cartoon by Jen Sorensen.

2. Concerns pertaining to arbitrators and decision-makers

States expressed their concerns on the legality of ISDS due to the fact that public-law disputes are considered by private persons - arbitrators. The system of party appointments, as well as the absence of a code of ethical rules raise questions about the independence and impartiality of arbitrators. Moreover, there is no possibility of appeal or judicial review of arbitral awards.

3. Concerns pertaining to cost and duration of ISDS cases

Monetary awards issued by arbitral tribunals during 2017 amount to sums from $15 million (Arin Capital and Khudyan v. Armenia) to $1.5 billion (MAKAE v. Saudi Arabia)[3]. However, besides the monetary award, the legal fees and related costs incurred by parties in investment proceedings were also excessive. As a result, in some cases, the governments had to spend significant amounts of money to defend legitimate public policies. Such a heavy burden especially effected low-income countries, which were unable to defend themselves properly against wealthy transnational corporations.

Arbitration proceedings would also be too lengthy. There may be a number of explanations for why the cost and duration of ISDS proceedings have become so high and lengthy[4]: complexity of disputes; behavior of the parties and their legal counsels aimed at delaying the process; delays in composing the tribunal and conducting the proceedings.

4. Other concerns

Besides these concerns, the delegates to the UNCITRAL Working Group III mention the lack of transparency in ISDS, disrespect of domestic procedures, etc.

How it may be fixed?

Given the problems with ISDS identified above, the delegates to the UNCITRAL Working Group III discussed options, such as (1)implementation of a systematic and multilateral reform through creation of a standing multilateral investment court or appellate body, and (2)improvement of particular procedural aspects of the existing ad hoc investor–state arbitration regime (further improvement of transparency, approval of code of conduct for arbitrators).

Such path of reform as the abolishment of ISDS as a form of dispute resolution altogether is not included in the WGIII agenda; though a number of NGOs and UN specialized bodies support this position.

The CIDS reported on analyses and road maps for the possible reform of ISDS[5]and recommended to UNCITRAL the implementation of a systematic and multilateral reform through creation of a standing multilateral investment court or appellate body. Both of these bodies would be composed of elected, qualified judges, which would not later act as experts and/or counsels.

On the one hand, the creation of both of these bodies would improve the consistency, predictability and legal correctness of investment awards, independence and impartiality of decision-makers and the credibility of ISDS in general.

On the other hand, the introduction of an appeal procedure would increase the costs and the length of proceedings, which are already expensive and long. In addition, it is doubtful whether there would be enough individuals with the proper qualifications, who could be appointed as a judge in a permanent body and would, at the same time, abstain from all other activities that could challenge his/her impartiality. Establishment of a permanent investment court or an appellate body also raises the question of the how to enforcement of the decisions of such bodies.

How could states fix the ISDS?

WGIII studied the issue of Transparency in ISDS from 2010 until 2016 and, although it partly achieved the stated objectives by adopting the UNCITRAL Rules on Transparency[6]and opening the Mauritius Convention[7]for signature, the effect of these documents on ISDS is quite limited. By comparison, we cannot expect to have effective results from the WGIII discussion on reform of ISDS soon.

Nevertheless, some of the states have already taken action to reform the international investment regime and ISDS. As delegates of states explained during the high-level IIA Conference (24 October 2018, Geneva), the negotiation of the text of the treaty is regarded more as a technical process, and therefore it is rather difficult to agree on innovative provisions. Mostly states use joint interpretations and apply subsequent practice in order to reform the existing regime.

The most vivid example of new reformed agreements is Netherlands Model BIT[8], which provides for a narrower definition of investor, the right of the host state to regulate in the public interest, enhanced transparency, appointing authorities for arbitrators, and no “double hatting”.

The Republic of Belarus, as well as most of the CIS states, does not have Model BIT, all the provisions are negotiated on a case-by-case basis. The most recent BITs of the Republic of Belarus dated 2010-2014 do not reflect any innovative provisions. During the last five years, Belarus directed its investment policy to the improvement of its domestic investment climate inter aliathrough modification of national legislation on investment.In 2013, because of the change in investment legislation, Belarus provided investors with the opportunity of applying to international arbitration tribunals for resolution of disputes, without previously applying to state courts. Curiously enough, the delegates of WGIII have mentioned that such opportunity shall be limited within the framework of the ISDS reform.

In 2018, Belarus faced three ISDS proceedings, as one may argue, as a result of this change in legislation. Taking into account the importance of this proceeding for the investment image of Belarus in the international arena, it is also interesting to see whether the recent developments could influence the course of such proceedings and consideration of the cases by arbitrators.

***

To conclude,at present, there is no specific roadmap for how to reform ISDS. From the discussions in WGIII, it is clear that there are differences of opinion among Delegations on how to act. Some advocate gradual change (Chile, Japan and the US). Others are openly supporting a multilateral investment court (EU Member States, Canada and Mauritius). And many remain undecided or undeclared (like Russia and India).

UNCITRAL Working Group III’s next session is scheduled to take place in New York from 1-5 April 2019 and will focus on preparing a work plan to develop solutions. This session will show whether UNCITRAL will focus on a single multilateral reform or a package of specific procedural reforms.

Ekaterina Shkarbuta

Junior associate at Sysouev, Bondar, Khrapoutski LLC

Coordinator at Young ADR - Belarus

[1]Possible reform of investor-state dispute settlement (ISDS), Note by the Secretariat A/CN.9/WG.III/WP.149, 5 September 2018 // Available at: http://www.uncitral.org/pdf/english/workinggroups/wg_3/WGIII-36th-session/149_main_paper_7_September_DRAFT.pdf

[2]Possible reform of investor-state dispute settlement (ISDS), Note by the Secretariat A/CN.9/WG.III/WP.150, 28 August 2018 // Available at: https://documents-dds-ny.un.org/doc/UNDOC/LTD/V18/056/80/PDF/V1805680.pdf?OpenElement

[3]Investor-State Dispute Settlement: review of developments in 2017, UNCTAD, June 2018 // Available at: https://unctad.org/en/PublicationsLibrary/diaepcbinf2018d2_en.pdf

[4]Possible reform of investor-state dispute settlement (ISDS), Note by the Secretariat A/CN.9/WG.III/WP.153, 31 August 2018 // Available at: https://documents-dds-ny.un.org/doc/UNDOC/LTD/V18/057/51/PDF/V1805751.pdf?OpenElement

[5]// Available at: http://www.uncitral.org/pdf/english/CIDS_Research_Paper_Mauritius.pdf

[6]UNCITRAL Rules on Transparency in Treaty-based Investor-State Arbitration, 1 April 2014 // Available at: http://www.uncitral.org/uncitral/en/uncitral_texts/arbitration/2014Transparency.html

[7]United Nations Convention on Transparency in Treaty-based Investor-State Arbitration, New York, 2014 // Available at: http://www.uncitral.org/uncitral/uncitral_texts/arbitration/2014Transparency_Convention.html

[8]Netherlands draft model BIT // https://globalarbitrationreview.com/digital_assets/820bcdd9-08b5-4bb5-a81e-d69e6c6735ce/Draft-Model-BIT-NL-2018.pdf